‘Thank you for altering the very meaning of life. From now on it is not dying we must fear, but living.’ — Arundhati Roy on nuclear weapons, ‘The End of Imagination.’

It is 5:28am on July 16th, 1945. Twenty-one days before the first bomb falls on Japan. Three weeks before Karlfried Graf Dürckheim hides himself away in Karuizawa. Six months before he dreams up his new mystical system in a Tokyo prison.

In an isolated location in New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto desert, less than a minute from now, American government officials will press a button and produce a defining moment for the 20th century spirit—the first ever atomic explosion.

The Trinity Test marked the first time that humanity detonated a nuclear weapon. Even with our species’ genius for violence, never before had we condensed such destructive power into a single device. Not since we first thought of the gods had we created something with such potential for terror and dread, a force that could deform the dreams and hopes of people everywhere.

The architects of the Trinity Test were physicists and engineers, mostly. Yet a few among them understood the religious or symbolic significance of their creation. And like Dürckheim, some of them translated this terrifying event, this eruption of death, into a new kind of spirituality.

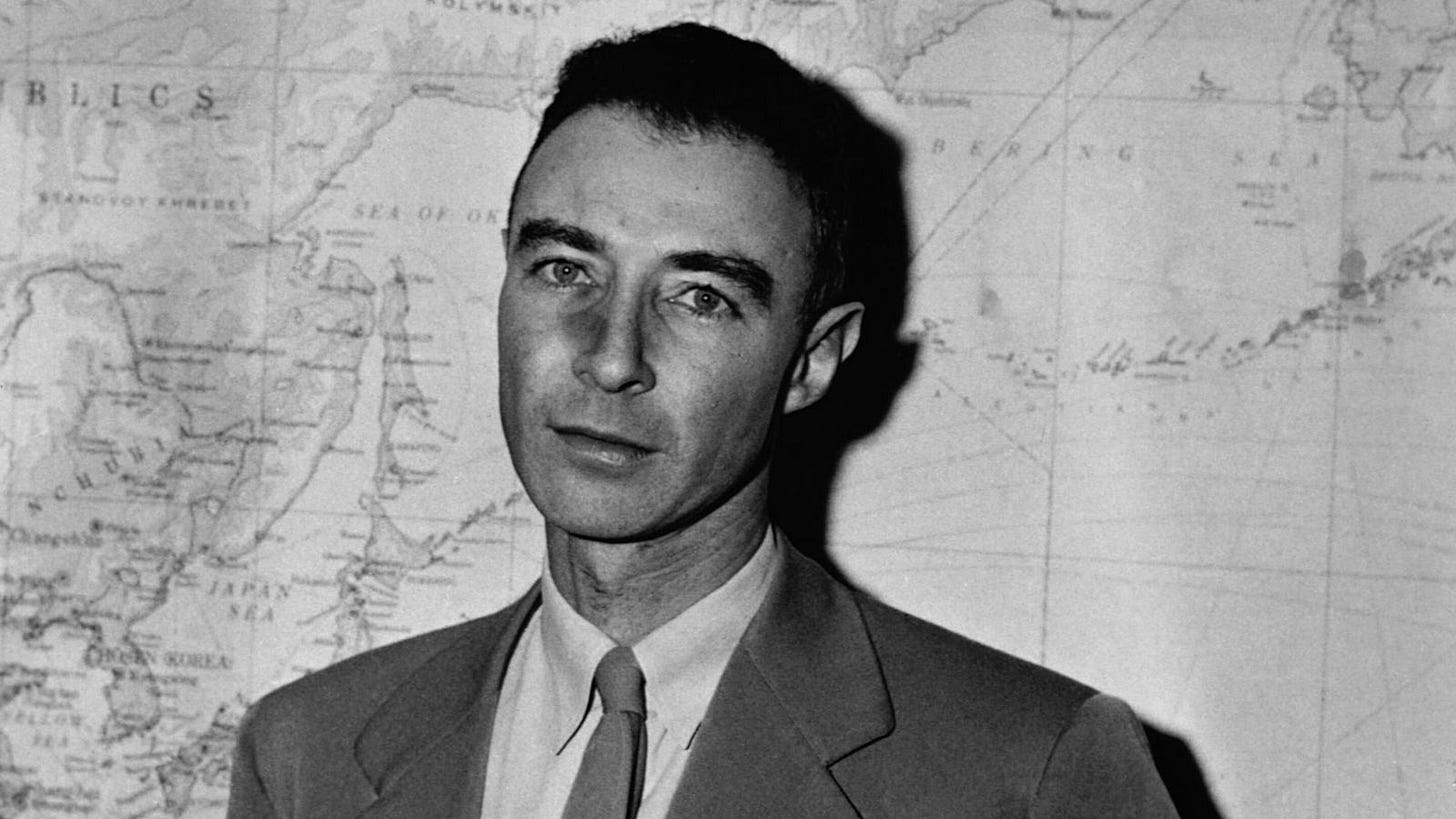

Robert Oppenheimer, a man once sent to a psychiatric ward after he tried to murder his university tutor in a cold, jealous rage who eventually became the lead scientist on this project of mass destruction, famously thought of verses from the Bhagavad Gita as the fire seared the sky. ‘If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one,’ he thought. ‘I am become Death, destroyer of worlds.’ Oppenheimer saw how his bomb united power and ingenuity and death in the greatest explosion ever seen. Engulfed by a sense of omnipotence and self-aware terror, he felt he had created a new kind of manmade god—a god of death, of annihilation, of disintegration.

The apparatus used to conduct the test was also pregnant with symbolic meaning. The bomb was detonated atop of a 100ft tall tower the scientists named ‘Zero;’ the ground beneath the tower they named ‘Ground Zero.’ After the bomb exploded in a refulgent flash, drenching the sky in light and purpling the clouds, both the tower and the ground were gone. With their bomb, the scientists erased Zero and the ground beneath. Logically, symbolically, all that remained was groundlessness. An absence transcending absence. After the test, and because of the names, a void that meant less than nothing remained: the fire burned away nothingness and vaporised its foundation.

Developing the bomb allowed America to defeat fascist Japan and end World War II. But their victory had a cost. For it meant that death and power finally triumphed. Destruction, and not virtue or life, became the organising force of human existence. The threat of an annihilation to come would now shadow everything. And an age of groundlessness began to unfold out from Ground Zero where pure positive force, instead of repressive negativity, became the defining feature of power.

All that followed was a reaction to this groundlessness. The negation of negation. Our age, we will see, is one of eternal return to this traumatic moment that ended fascism, but which would eventually demand its repetition.