Mutually Assured Destruction (or, Duck and Cover)

Chapter II, Part III - The Myth of the 20th Century

As news of the bomb echoed soundlessly, endlessly, around the world, its flash translated into the spectral light of TV images and the disembodied sounds of radio speech, reiterated with words and ink on paper designed to decay, people did not know how to react. It took time for our new imaginary to develop; perhaps this is because the bomb blasted open a paradoxical place in our minds.

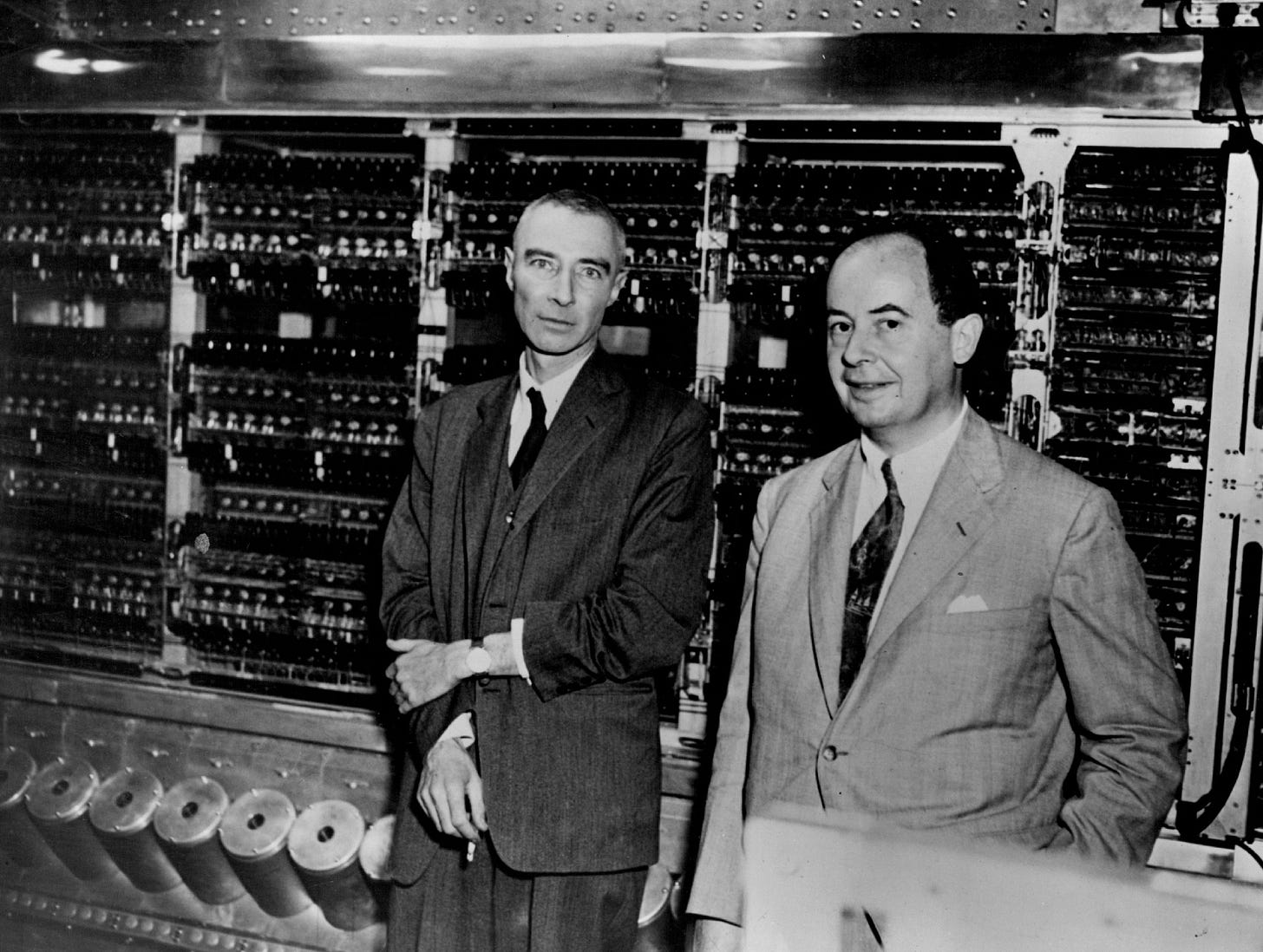

The bomb’s paradoxes were first perceived, perhaps, by one of the bomb’s key desingers—mathematical genius John von Neumann. Von Neumann worked for years on the bomb: he designed its mechanisms, he calculated likely death tolls, he advised the US on how they might deploy it for maximum destruction. Yet at the same time, he also published an important book, 1944’s Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour, which helped establish the branch of mathematics he later used to explain why nuclear war would only end with mutually assured destruction. Von Neumann built the bomb and helped to deploy it in Japan; he also explained why nuclear war could not occur. He willingly contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands; he insisted the device he designed could never cause the harm it threatened.1

Von Neumann’s predictions have been vindicated—so far. The Soviets developed their nuclear capability in 1949; the bombs have not been used in war since. Despite moments like the Cuban Missile Crisis and other nuclear close calls—there were at least eight in the 1960s alone—the logic of mutually assured destruction has worked as von Neumann had predicted. Because we all had nukes, the nukes have not been launched. Creating the means for nuclear war has ultimately prevented it.

John von Neumann’s legacy is like his mind: a strange, yet rational contradiction. After Hiroshima, he suggests, the only way to achieve peace was by creating the most credible and destructive threat imaginable. The only way to protect freedom and civilisation was in an endless, compulsory scramble towards violence, death, and barbarism. The bomb started a race we believed we were forced to run but whose destination, we hoped, we would never reach. An infinite pursuit and deferral of extinction and the abyss. It birthed a dream of annihilation, always coming, never arriving; a thought of the end of meaning that rewrote the meaning of life.

Once created, the bomb became necessary and impossible all at once. Somehow it was both reality and dream—a dream that had the strange power to remake reality.

After Hiroshima, a force entered the world that drove us towards terror and annihilation; at the same time, it infinitely and indefinitely postponed our destruction. Beneath our death-to-come, our nightmares of the blinding light that would end everything, our ideals were transmuted into their opposites. Living under von Neumann’s logic of M.A.D., peace became total war. Life was preserved through the spectre of utter annihilation, the greatest death threat imaginable. Science was finally seen for what it was—a doubled-edged blade of progress and of destruction. Our grand desires for human enlightenment, liberty, and peace, were revealed as a route into death, extinction, oblivion.

Beneath the threat of mutually assured destruction, author Thomas Pynchon observed that atomic war quickly became the ‘common nightmare’ of people everywhere. ‘Except for that succession of the criminally insane who have enjoyed power since 1945, including the power to do something about it,’ he once wrote, most of us have been ‘stuck with simple, standard fear,’ a terror we dealt with ‘in the few ways open to us, from not thinking about it to going crazy from it.’ Pynchon himself chose a masochistic option: he assumed a pose of ‘somber glee at any idea of mass destruction or decline.’ Others, perhaps stupefied by the thought of annihilation, did not respond and continued as if nothing had changed.2 Meanwhile, a young woman in a psychiatric hospital told R. D. Laing that she was terrified that the Bomb was inside her; our shared nightmare had rewritten her mind and being at the atomic level.3 Perhaps she was the least mad of them all. The bomb’s threat was totalising, after all; as a spectre of the future, a fiction that was nothing and nowhere, the bomb haunted everything and everywhere. ‘On the day of reckoning,’ Arundhati Roy wrote, the ‘devastation will be indiscriminate. The bomb isn’t in your backyard. It’s in your body. And mine.’4 After the bomb, every cell of the body could only exist because the thought of its destruction loomed on time’s horizon, violating the boundary between being and nothingness.

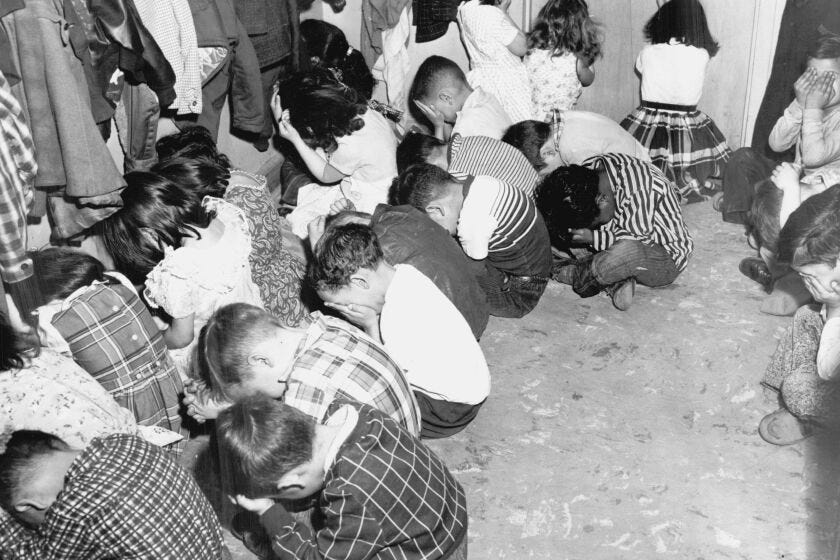

The bomb entered our bodies in every way imaginable—through sight and image, sound and silence. For children, the education system played a vital role. Government mandated “duck-and-cover” drills became a regular fixture of school life. During a lesson, a bell would ring and teachers would tell children to hide under their desks or crouch in their corridors. The idea was to protect the children: to shield their eyes, their ears, their bodies against any nuclear blasts close enough to harm them but too far away to destroy them. The pragmatic value of these drills was debatable. Some have since argued that they were a means of reassuring the population that the government had a plan in the event of nuclear war; that the authorities were not powerless against death.5

In a way, the drills were an instrument of mass hope – their purpose was spiritual. Yet as the children crouched with their hands over their faces, collapsed into the foetal position or prostrate on the floor, many instead learned the opposite: they realised that nothing and nowhere was safe. That death could fall from the sky at any instant, erasing them and the ground they lived upon in a blast of light. Far from being a lesson in survival, the drills attained an almost religious, mythical significance: a mass for the 20th century. As the drills interrupted the children’s morning prayers, science classes and civics lessons, they impressed a negative hope, a deep anxiety upon the children. They showed that blunt power now ruled the world. That a religion of terror could thwart the love of God or country or humanity. That war could no longer be fought in the name of life, but only for something beyond life—death, nothingness.6

Shadowed by the god of groundlessness, a fear of the bomb, of a destruction that did not and may never exist, soon took precedence above all else. Written in the air—written in the black ink nobody could see but nobody could forget—was the ‘myth of the 20th century’.

References

Derrida, J. (1984) No Apocalypse, Not Now (Full Speed Ahead, Seven Missiles, Seven Missives). Diacritics, 14(2): 20-31.

Laing, R. D. (2010) The Divided Self. London, Penguin Classics.

Roy, A. (1998) ‘The End of Imagination.’ Retrieved from: https://www.spokesmanbooks.com/Spokesman/PDF/68roy.pdf

Footnotes

https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/john-von-neumann/

The Divided Self, p.12.

https://www.spokesmanbooks.com/Spokesman/PDF/68roy.pdf

See https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/duck-cover-nuclear-war-plan.html

https://www.ens-lyon.fr/sites/default/files/2018-09/Derrida%20No%20apocalypse.pdf