In the 1950s, the threat of the bomb dissolved the boundaries between sex and violence, pleasure and terror, entertainment and anxiety.

Earlier in the century, psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud had shown how our sexual and aggressive instincts were held in place by our ideals: humans redirected their antisocial forces into moral self-constraint and their efforts to actualise their ideals, a process Freud called ‘sublimation.’ By causing the collapse of our beliefs and ideals, the bomb freed these instinctual energies, which could now pursue their original targets—sex and violence, or the sadomasochistic blending of the two. Sexual liberation followed, and it is no surprise that the sexual revolution began only twenty years after the Trinity Test. But at the same time, as political theorist Wendy Brown has discussed, this desublimation lessens the power of human conscience. The casualties include our general concern for others and our ability to delay gratification or restrain ourselves to preserve future generations of humanity.1

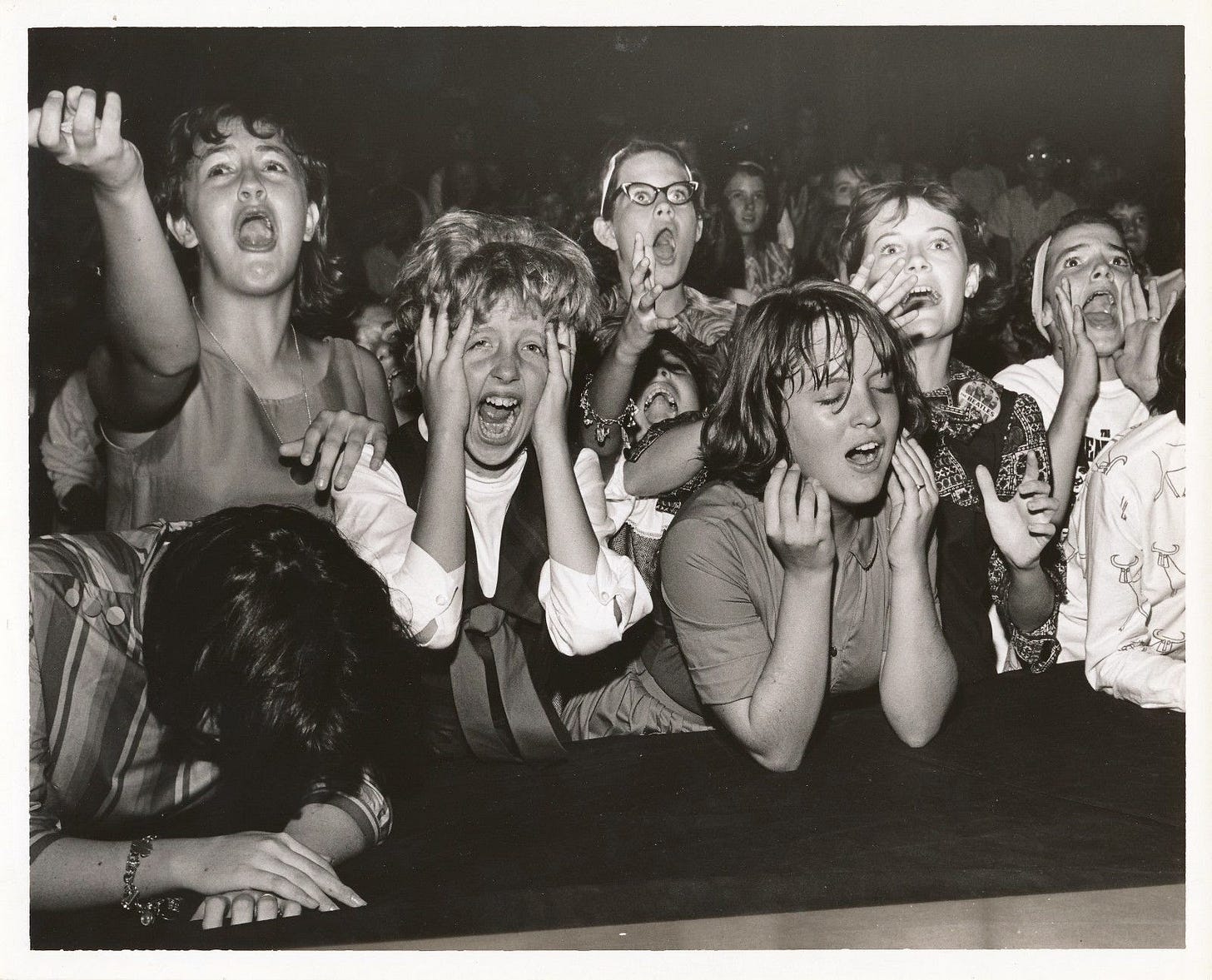

A sense of immediacy thus emerged in our culture of the bomb. Cultural critic George Steiner once observed that the threats of mass death and extinction that emerged in the 20th century—the bomb, but also the world wars, the concentration camps, the gulags—destroyed our belief that the future would be better. The spectre of death killed our utopian dreaming. In the wake of these atrocities, we no longer experienced history as ascendant; moreover, the only form of immortality known to humans—our preservation in memory and culture—was placed in jeopardy. The future was now in peril—no longer would people sacrifice the present for what might come tomorrow. No longer could people gamble on transcendence. No longer would we live in a world where the horizon of meaning stretched indefinitely into the distance; meaning instead might vanish entirely in a white flash of heat. Labouring beneath the presence of death, people turned away from the future toward what Steiner called a ‘utopia of the immediate’ where impulse, desire, intensity and rapid satisfaction reigned supreme.2 This nihilistic utopia, of course, finds its most immediate expression in the consumption culture that exploded in the 1960s—a culture dependent on the rapacious extraction of resources from deep within the Earth, on a demand for another kind of groundlessness whose ecological consequences would eventually threaten the very grounds of our world’s social systems.

Against these nihilistic forces, others engaged in Apollonian denials of reality. Some became indifferent and apathetic to the danger; others fetishised it or adopted ironic attitudes towards destruction. For Salvador Dalí, the ‘terror’ he felt after Hiroshima led him to obsess over the bomb. The ‘atom’ soon became his ‘favourite subject of reflection,’ and he elaborated a form of ‘nuclear mysticism’ that he felt would allow him to ‘gain control’ over the world’s ‘hidden laws.’3

Others responded to their terror as philosophers always have, developing new philosophies that defended the meaning of life against nihilism. There is a reason Viktor Frankl’s Holocaust memoir, Man’s Search for Meaning, became a bestseller in post-war America. Much like Karlfried Graf Dürckheim in his Japanese prison cell, people were desperate for hopeful ideas that could displace or deny the fear of loss or death that ravaged their minds.

Even more bafflingly, given the origins of the bomb, others redoubled their commitment to scientific progress. Driven by Cold War geopolitics, absurd and grandiose projects were planned, the US government’s ‘Project A119’ perhaps foremost among them. Project A119’s goal was simple: to demonstrate to the world the power of their military technologies and their cultural supremacy, the US government planned to nuke the moon. Project manager Leonard Reiffel said the intention was to create a mushroom cloud that would reach upwards from the lunar surface to be lit from behind by the sun. The explosion was to be so large that it would be visible from earth to the naked eye. Project A119 is a sign that US officials understood the symbolic meaning and power of the bomb. By firing their missiles, phallic objects, into the moon, a maternal symbol, they could create an awesome, dreamlike image of destruction, and the world would know they were ruled not by goodness or justice, but by pure, violent force.4

Project A119 was inevitably abandoned. The US government deemed the risk of the nuke falling back to earth to be too high, and they redirected their efforts toward safer ways to demonstrate the powers and precision of their rocket technology. Most significant here was the space race. Hoping to capture the public’s imagination, in 1962 President Kennedy announced a new spiritual quest for America: he declared that man would land on the moon before the end of the 1960s. With his idea, he spoke to the spiritual yearning of a nation that had lost its beliefs and had nothing to replace them. So began the Apollo missions, a thinly veiled demonstration of America’s missile supremacy, designed and led by former Nazi scientists like Wernher von Braun. NASA started to train astronauts in the craters left by nuclear tests, which resembled those on the moon’s surface. And, as if in an unconscious admission of the link between these projects, NASA launched its mission to the moon on July 16th, 1969—24 years to the day after the Trinity tests.

Four days after the launch, men had walked on the moon and the world was amazed. Yet the fanfare concealed something more important and disquieting. Hannah Arendt once wrote that overcoming our earthbound nature would be among the most profound changes to the human condition conceivable.5 When they travelled to the moon, the astronauts accomplished this change: they dwelled in the void for days between their departure and their arrival. And floating in their spaceship, looking across the vast and dark expanse between themselves and Earth, they discovered a psychic groundlessness that mirrored the spiritual one that motivated their efforts.

Actor William Shatner gives an exemplary account of this psychic groundlessness. During his trip to space, Shatner looked out the window into the blackness. Instead of the mystery, majesty or awe he believed the sight would inspire, ‘all [he] saw was death;’ all he felt was ‘dread.’ Turning back toward Earth, hovering in the void, a funereal sadness consumed Shatner as he sensed our planet’s fragility and the brute violence humanity inflicts upon it every day, driving it ever closer to destruction.6

Shatner doesn’t mention the bomb in his recount. But we can’t help but wonder if the bomb was on his mind. Between the images of Earth suspended in the void, and those of the hollows in the ground we gouge out with nuclear blasts, between the ‘pale blue dot’ and Hiroshima, we catch a glimpse of the 20th century’s most traumatic thought—the contingency of everything, the possibility of nothing.

References

Arendt, H. (1958) The Human Condition. Chicago, IL, The University of Chicago Press.

Brown, W. (2019) In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Anti-Democratic Politics in the West. New York, Columbia University Press

Steiner, G. (1971) In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards the Re-Definition of Culture. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.

Footnotes

In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, pp. 162-167.

In Bluebeard’s Castle, chapter 3.

https://www.salvador-dali.org/en/research/archives-en-ligne/download-documents/16/salvador-dali-and-science-beyond-a-mere-curiosity

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/usa-wanted-to-nuke-the-moon.html?firefox=1

See The Human Condition

https://variety.com/2022/tv/news/william-shatner-space-boldly-go-excerpt-1235395113/