You may have never heard of human capital theory. Nevertheless, it has probably affected your history, your being. It has colonised your future. Warped your potential.

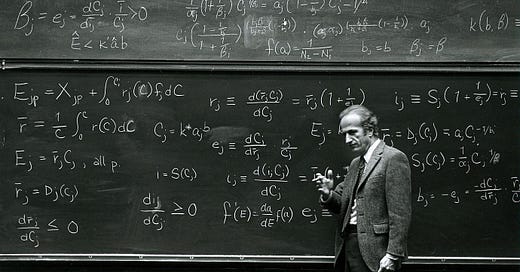

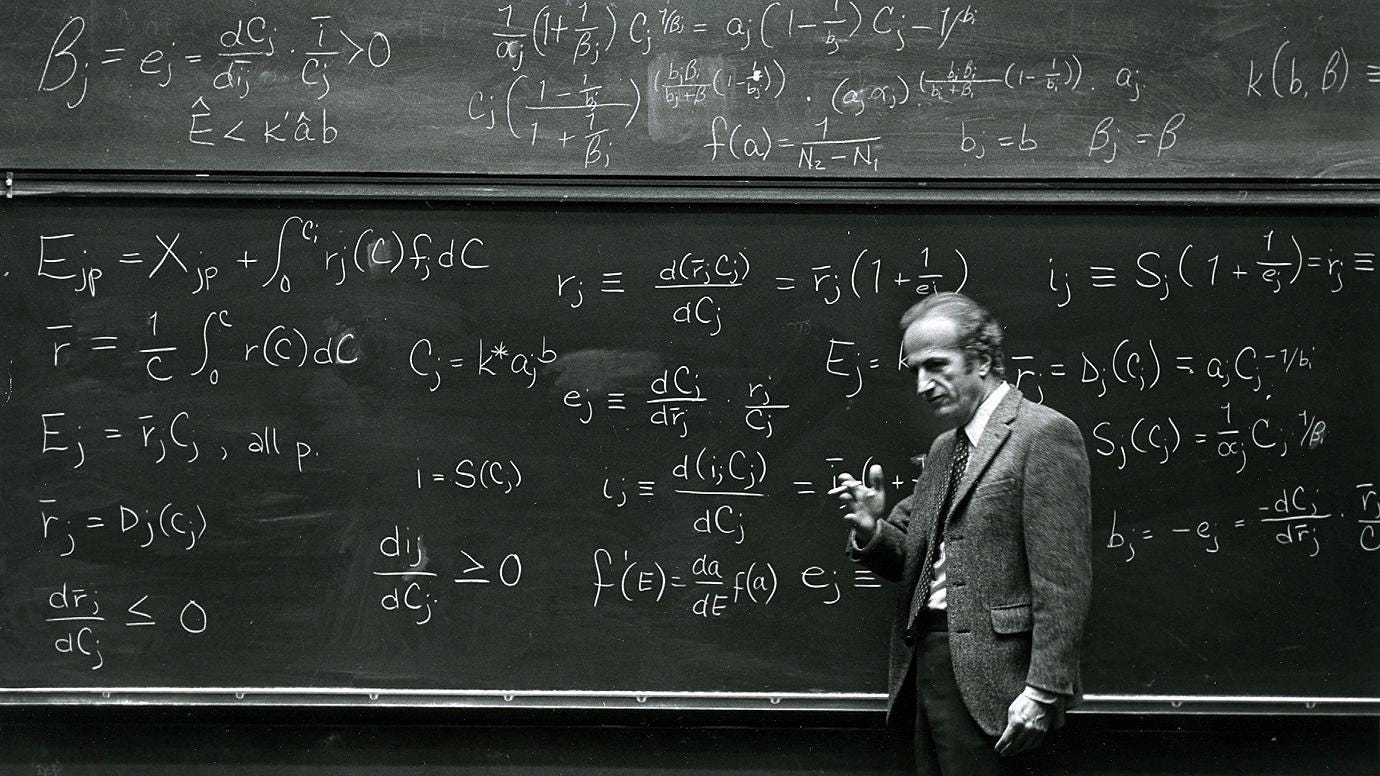

During the 20th century, economists like Gary Becker ushered in a new era of economic theory with three surprisingly banal observations. From the classical period onwards, economists’ models had never accounted for differences between workers. This was obviously deficient. As Becker and his colleagues saw, workers need specific abilities to succeed in specific roles. Moreover, workers are not equally endowed with these abilities. Nor are they equally productive in every role. Buoyed by these insights, they posited that every worker has different attributes that influence their productivity.1 Our knowledge, talents, health and social skills2 also determined the output of our production, our wages and society’s overall economic structure.3

Becker drew some simple conclusions from these insights. To capture the world accurately economists first had to recognise that ‘people invest in themselves.’ They also must acknowledge that these investment decisions lead to significant differences in workers, productivity and wages,4 and include such investments in economic analyses. These arguments are obvious enough. But it was in pursuit of these ends that Becker proposed a radical, new concept. Investments in learning and skills, Becker said, ‘yield income’ and output ‘over long periods of time.’5 Much like investments in machinery and land, investing in knowledge and self-development—in extracting the ‘real information’ flooding from the ‘ground of Being’—generates economic profits. A worker’s endowments, then, were effectively a form of capital – ‘human capital.’

Becker’s detractors said human capital was merely a ‘specious synonym for labour.’6 Despite their protests, the idea proved influential. First articulated in the early ‘60s, his concept soon ascended to the mainstream of academic and economic life. In its wake economists rethought all self-improving activities, from education to healthcare, in terms of their benefits for human capital. By the century’s end Becker had won a Nobel prize. Following his wisdom, our society had also started telling workers to become ‘capitalists of themselves.’7

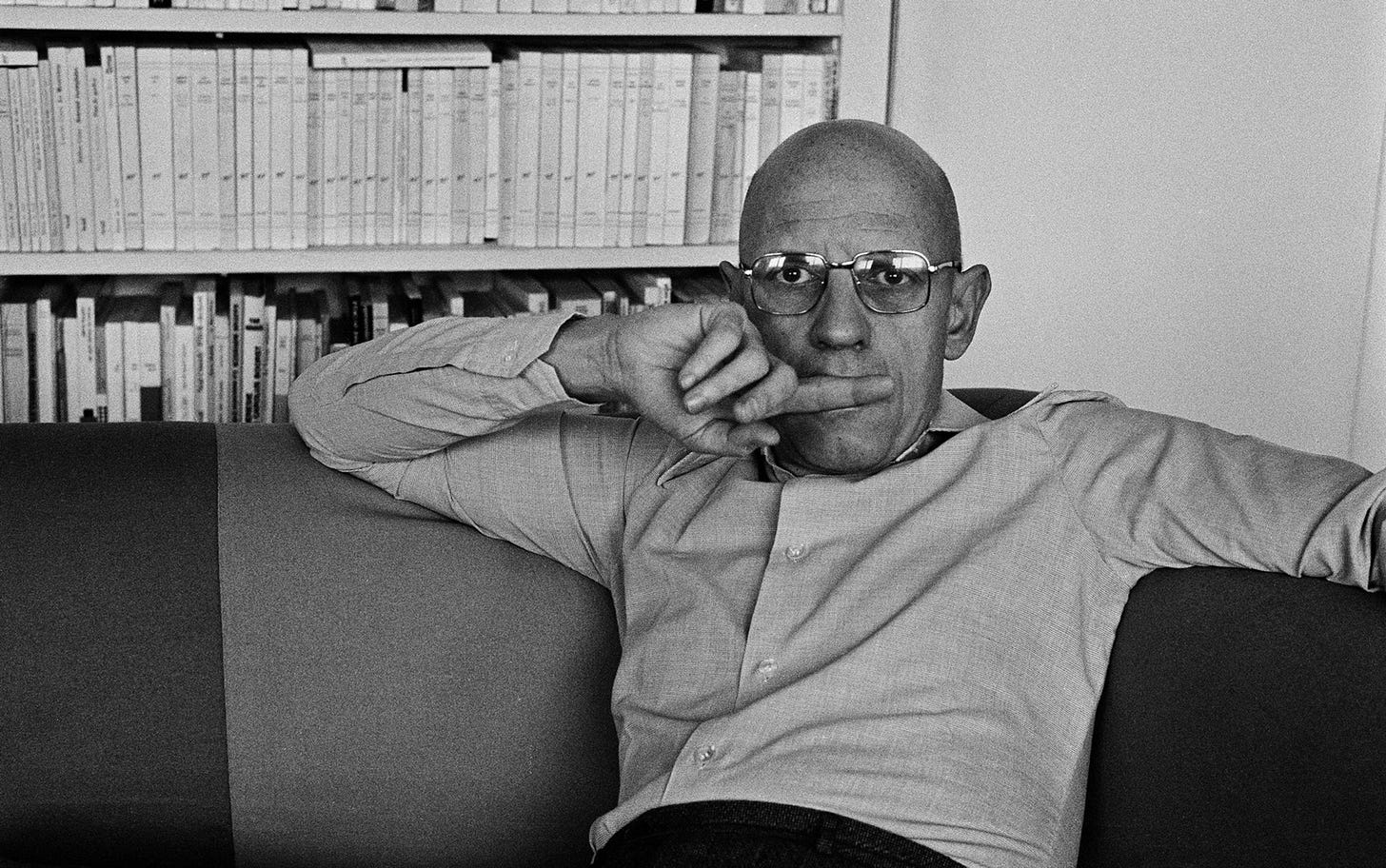

Michel Foucault once described how human capital theory gave us a new way to understand ourselves. If knowledge and skill turn us into capital, Foucault said, our bodies are essentially ‘ability-machines.’8 Seeing ourselves as profit-generating ability-machines, we quickly discovered our incentive to maximise the returns on our investments. We understood the need to optimise the processes where we take the raw inputs of perception and turn them into valuable assets. As utility-maximising economic actors—as ability-machines—we rationally became obsessed with visions of ourselves flourishing at the highest capacity, achieving all we can by exploiting the ‘real information’ congealed within as human capital. It was optimal and efficient, we saw, to develop a fetish for potential. An addiction to possibility.

‘Human capital’ is an immensely flexible idea. In his Nobel lecture, Becker said he used ‘the economic approach to analyse social issues that range beyond those usually considered by economists.’ Such analyses were also made possible by his assumption that every action was a utility-maximising decision.9 Becker’s work was an intentionally totalising application of economics. With his innovation, we gained a concept we could use to subject every aspect of human existence to the rationale of market economics. Now ‘human capital all the way down and all the way in,’10 economic logic demanded that we accumulate skill and knowledge, burdening us with an imperative to flourish. Workers were commanded to realise their dreams and work jobs they loved,11 for this would yield them a surplus of ‘psychic income’ – something once known by that archaic term, ‘enjoyment.’12 Manifesting our potential would be good for business, too, so we were told to be ambitious and strive after ‘good’ jobs. Some realised their relationships and acquaintances—their ‘networks’—affected their ‘capital stock,’13 and worked to optimise the yield of human interactions. Physical and mental health became measures of asset quality—hence the rise of wellness culture, nootropics and psychotherapy—while ageing, decay, madness, sickness and death became debasing anti-capitalist forces. No longer ends-in-themselves, education and cognitive capacity became our most important assets for success both economic and existential. The economic and existential also became identical. ‘Business ontology’ subsumed all.14

Or, as Dagmar Herzog writes on p.253 of Sex After Fascism, shifts in sexuality in the late twentieth century revealed among people a growing ‘tendency to find the “ego trip” of narcissistic self-display at least as exciting as the physiological sensation of orgasm, and an attempt to optimize the time investment in sexual encounters so as to make them less disruptive of the pursuit of career achievement.’

In the mid ‘00s, Kanye West released three education-themed albums that rebuked his culture’s rigid expectations that he would go to university. Even Kanye’s ambitions were colonised by human capitalism.15 This should come as no surprise. Human capitalism changed everything in our society: academia, government, business, our visions of human potential and, finally, the ‘meaning of being human.’16 Human capitalism co-founded a new kind of subjectivity—we are now what Slavoj Žižek calls ‘hedonist subjects’ whose ultimate values are self-reinvention, identity fluidity, and achieving our potential—and revolutionised the ethics and morals of our society.17 In its shadow what matters is not our innate dignity but achievement, learning and possibility. Every second the human capitalist can always do more, become more. If we fail to do so, the shame and guilt—the irrationality, the waste—is ours alone.

Human capitalism established a new totalitarianism of the soul. An ethic of total-work. Shackled to imagined futures of achievement and individual prosperity, and dominated by self-centred ambitions and fears of inadequacy, we became addicted to possibility. We began to believe in a strange kind of freedom where we were compelled to be the best, most authentic versions of ourselves. Desire and compulsion became inextricable from one another; society demanded that we do what we loved. In Mark Fisher’s words, we no longer believe in freedom from work but in freedom through work.18 In Arbeit Macht Frei. Freed into self-subjugation, the addiction to possibility now masquerades as the very limit of human freedom. ‘Manifest your potential!’ – these are the words that colonised our future.

Footnotes

Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, p.324.

These traits are determined by our innate ability, schooling and training. Sam Bowles and Herb Gintis, also include ‘manner of dress, speech, personal demeanour and life-style, self-concept and status identity’ and ‘work-relevant personality traits like resignation to or approval of the structure of control and distribution of rewards in the enterprise, dependability and orientation to authority within this structure, and propensity to respond individualistically to incentive mechanisms’ in the list of traits that constitute human capital. IQ is also a relevant trait. Yet, as some critics note, this opens human capital theory to use and abuse by racists, who insist on explaining economic inequality with reference to racial and ethnic differences in IQ.

See Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1975) The Problem with Human Capital Theory—A Marxian Critique. The American Economic Review, 65(2), pp.74-82. See also Acemoglu & Autor’s Lectures in Labor Economics, pp.3–8.

Schultz, T. (1961) Investment in Human Capital. American Economic Review, 51(1), p.2.

Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, p.15.

See the entry on ‘human capital’ in Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism. The relevant excerpt is also available here: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/the-problem-with-human-capital/

Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism.

The Birth of Biopolitics, p.226.

Becker, G. (1993) Nobel Lecture: The Economy Way of Looking at Behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 101(3), pp.385-386.

In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, p.163.

As Erin Griffith wrote in a New York Times article called ‘Why Are Young People Pretending to Love Work?’ the yuppy today ‘never exits a kind of work rapture, in which the chief purpose of exercising or attending a concert is to get inspiration that leads back to the desk.’ She also sees that in our ‘new work culture, enduring or even merely liking one’s job is not enough. Workers should love what they do, and then promote that love on social media, thus fusing their identities to that of their employers.’

The Burnout Society, p.26, and Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, pp.11 & 16.

Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism.

Capitalist Realism, p.17.

See the kind of obnoxious ‘School Spirit’ skits on The College Dropout.

See Julia Karp’s article, ‘Human capital ideology’: https://twothousandhappynations.org/human-capital-ideology-is-neoliberalisms-last-line-of-defense

See the preface to Myth & Mayhem: A Leftist Critique of Jordan Peterson.

See Mark Fisher’s unfinished piece, ‘Acid Communism.’