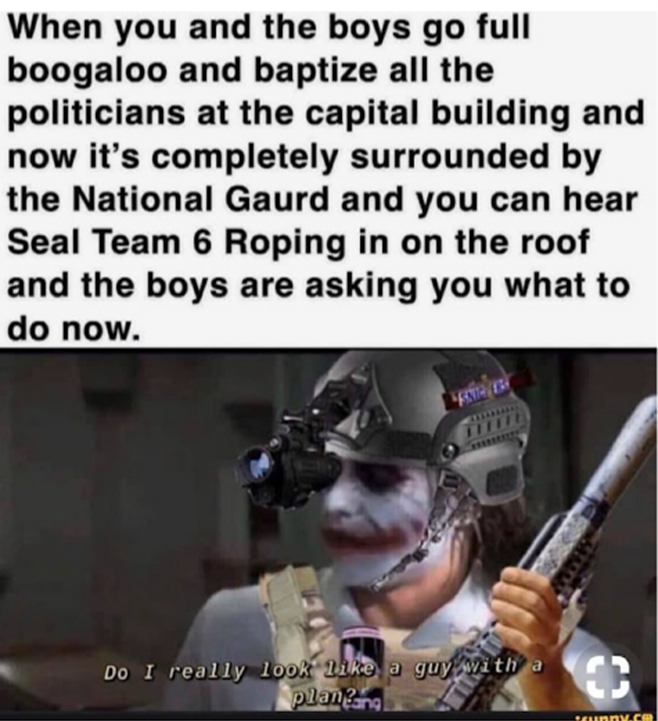

The Boogaloo Bois are an armed, pro-Trump militia that appeared at the riot at the United States Capitol in Washington D.C. on January 6th 2021. The following is a meme shared on a Boogaloo Bois Facebook group in 2020:

The meme is eerily prescient and entirely weird. It seems to predict the attack long before it has actually happened, yet the seriousness of its Nostradamus-esque foreshadowing is subordinated to a strange register of ironic esotericism. There is a political meaning translated here, but it is idiosyncratic and strange. Its traditional political import is eclipsed by its enmeshment with the self-reflexivity of internet discourse.

If we are to understand January 6th and Trumpism in general, we must understand how this meme transmits political meaning.

The trouble with the meme begins if we try to explain it. Let’s begin with a simple description. The meme is comprised of two sections. The bottom section shows Heath Ledger’s depiction of the Joker in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008). Superimposed onto the character is military gear taken from the popular 2012 video game Counter Strike: Global Offensive, as well as a Snickers bar and Bang soda can. The text at the bottom of the image reads ‘Do I really look like a guy with a plan?’, a quote from Nolan’s film. The top section of the meme is dominated by text that communicates irony and political violence. The Joker, CS:GO, Snickers, soda, boogaloo, ‘baptising’— what is going on here?

To track the various sources that coagulate onto this piece is to commit to a form of reading we call hermeneutics. It is the kind of reading we are all used to. It is the surface-depth process of interpretation we are taught in English classes, the same process that is jokingly skewered in the below meme:

Hermeneutics takes the surface presentation of things at face value, and picks it apart to show that the animating force behind that surface—what it really means—occurs under it, between the lines. But is there anything occurring under the surface of the Literature teacher meme? Or behind the Boogaloo meme? To try and hermeneutically read these pieces—to try to explain why the Joker ends up in CS:GO military gear, or why that Shrek-looking thing ends up as an English teacher—misses the process by which the meme creates meaning. The hermeneutical approach is merely the recognition of sources as opposed to an elucidation of meaning. We do not get a clear message in the meme as much as a coordination of various references that produces humour.

The creation of the meme’s meaning, then, is done so via a network of sources that come together onto the artefact. Terminologically we can call this tendency, following Deleuze and Guatarri, rhizomatic. We can understand this term as Byung-Chul Han defines it: ‘an open structure whose heterogenous elements constantly play into each other, shift across each other and are in a process of permanent “becoming”’.1 A meme grabs stuff from the ‘internet of things’ and recasts them to create content. The deeper you go into online subcultures, the more stuff there is to grab, and the weirder and stranger things become. Eventually, they become impenetrable without an intense amount of prior knowledge, even to those within the subcultures themselves.

Memes operate at a surface level. They take different symbols, tropes and references and link them together to produce an affect. Affects are like emotions, but they are easily spread from one person to another. They can be feelings like fear, humour, insecurity, anger and so on. Memes are engines of affectual coordination as opposed to machines of surface-depth meaning creation. Meaning as such is bottomed out in the meme, leaving us with a meaning-making economy that prefers affect over substance. Feeling trumps politics.

How does this pertain to Trumpism? Trump’s is a heavily affectual form of politics. His is not a politics of meaning in the traditional sense, but instead a politics of feeling. We can see this in Trump’s speech-making. Where a speech from John McCain, Mitt Romney or even Ted Cruz will be a carefully constructed piece of rhetoric, Trump’s is all bluster and posturing. As Lauren Berlant writes: It is ‘the noise in [Trump’s] message’, that ‘increases the apparent value of what’s clear about it. The ways he’s right seem more powerful, somehow, in relief against the ways he’s blabbing.’2 The economy of meaning that Trump exploits is as far away from the logical as you can get. His resonances with conspiracy theories as far flung as Pizzagate and QAnon indicate that this tendency, what we can call a memetic tendency, dominates in Trump’s base.

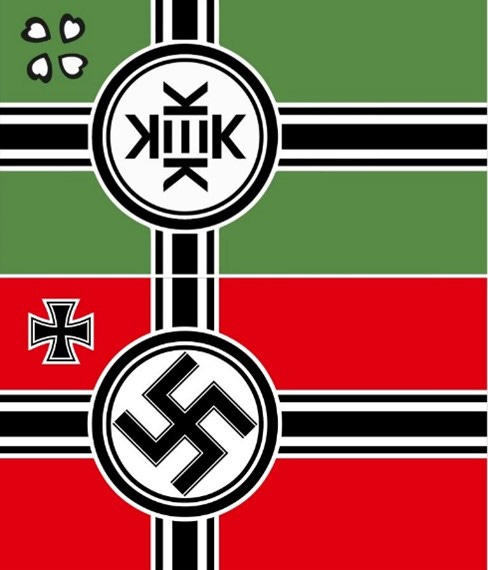

To close I will offer a real-world example from the January 6th attack. Below is an image of two men wearing the flag of Kekistan:

Kekistan is a fictional country made up in reference to the Egyptian god Kek. Kek is usually associated with notions of chaos and darkness, and is sometimes depicted as a frog. The significance of Kek’s depiction as a frog coincides with the far-right adoption of Pepe the Frog as a symbol or in-joke for racist trolls, while the word kek means ‘LOL’ in gaming culture, particularly in the video game World of Warcraft. In a further rhizomatic link to the far-right, the flag appropriates a Nazi wartime flag for its design:

As with the Boogaloo meme, to understand the flag of Kekistan leads to a set of disparate sources that, beyond their origins in a highly digital form of discourse, do not come together around a coherent politics. The politics of Kekistan, then, are highly incoherent, perhaps utterly illusory. Yet the presence of the flag indicates a political important along those very lines. Incoherence dominates, but is represented in the performative register of coherence: designing the flag, bringing the flag, presenting the flag. The implicit assumption that those around will recognise the flag as politically significant speaks to a misrecognition of the highly incoherent meaning-making economies of the digital as productive of a coherent politics.

To understand Trump and his specific form of digitally-mediated politics, we must first come to terms with the fact that Trumpian politics lacks substance. Its game is not played in the political arena as commonly understood. Any opposition to Trump must take seriously the task of supplementing effective policy with the coordination of affect.

See the full list of guest posts.

References

Byung-Chul Han, Hyperculture trans. by Daniel Steuer (Cambridge: Polity, 2022), p. 27.

Lauren Berlant, ‘Trump, or Political Emotions’, The Critical Inquiry, 5 August 2016 <https://thenewinquiry.com/trump-or-political-emotions/>