Ruled by the logic of consumer capitalism, Bowie’s art is explained by a coeval economic theory – Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of ‘creative destruction.’ In 1943, four years before Bowie’s birth, two years before the bomb Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter published a book called Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Its subject was the dynamics of capitalist societies – how they grow and shrink, how they produce or destroy wealth. It said nothing of music and little about art. Yet one of Schumpeter’s ideas explains something critical about Bowie’s art. It was his notion of ‘creative destruction.’

Unlike economists before him, Schumpeter saw that capitalist societies do not grow in a linear, continuous or peaceful way. Economic productivity instead rises through violent breaks, where innovation and technological changes displace or destroy the existing ways of making and doing. Industrial mutations, Schumpeter said, ‘incessantly revolutionise the economic from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.’1 The horse-drawn cart died so the automobile could rise, just as factory lines killed artisan labour. Similarly, the blinding, Vegas-like lights of Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour only burned because the Japanese city was first blasted in the war. The same goes for Germany’s incredible post-war economic growth. ‘The German economic miracle,’ writes George Steiner in a book that influenced Bowie, ‘is ironically but exactly proportionate to the extent of ruin in the Reich.”2

To create wealth we must also destroy it – this is the violent antagonism that underwrites capitalist society. ‘This process of Creative Destruction,’ writes Schumpeter, ‘is the essential fact about capitalism.’3 The ‘perennial gale of creative destruction’4 buffets all industries, threatens all technologies and attacks all social relations. This force marks all eras of capitalism. Yet it is unignorable in the post-war decades when Bowie came of age, where capitalist growth relied on society’s rapacious appetite for new styles, new fashions, new experiences. As both a producer and consumer of music, Bowie’s ‘insatiable need to keep up with the ebbs and flows’ of ‘modern pop’5 reflects this violent dynamic.

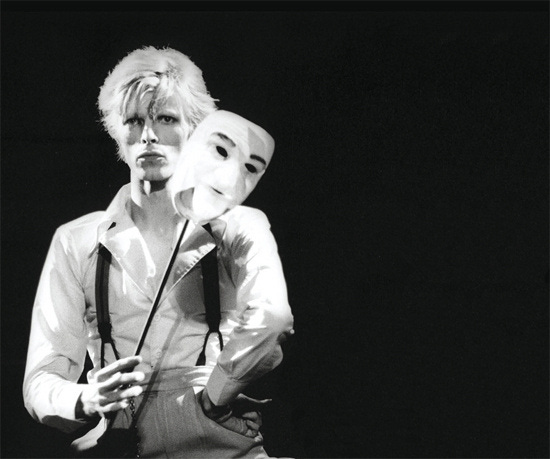

Consumer capitalism demands relentless change. For artists who crave prolonged commercial success, then, an unstable identity is an asset. By 1973 such instability had long been one of Bowie’s talents and traits. ‘There is no definitive David Bowie,’ he once said, ‘My style is changes.’ Elsewhere: ‘I’ve learned to flow with myself. I honestly don’t know where the real David Jones is.’6 Only a few years after Jacques Derrida’s annus mirabilis, then, Bowie had refashioned himself into something that embodied the movement of différance. Ziggy’s death only radicalised this instability. Afterwards ‘Bowie, almost ascetically, almost eremitically, disciplined himself into becoming a nothing,’ Simon Critchley writes, ‘a mobile and massively creative nothing that could assume new faces, generate new illusions and create new forms.’7

Schumpeter once wrote that capitalism ‘not only never is but never can be stationary.’8 The same applies to David Bowie. Like capitalism, Bowie contained a ‘restless nothing’ within, a creative void that both destroys and creates, giving vitality to its subjects through disintegration.9 The same groundlessness lives at the heart of the man and his society. Bowie’s art reveals how we can exploit such self-instability to achieve economic success. Yet the same instability both produces and results from anguish, exhaustion and trauma, too.

Predisposed to this instability, Bowie was not immune to such sufferings. A Rolling Stone piece on Bowie’s childhood notes that the artist was ‘born with a need to move on’—a consequence of the adverse environment he was born into.10 By many accounts, including Bowie’s own, he grew up in a troubled household filled with ‘emotional and spiritual mutilation’. His mother was a cold and unaffectionate woman—according to Angie Bowie, David and his mother would apparently ‘peck at each other like psychotic vultures’ when together—and some biographers claim she was mentally ill or borderline schizophrenic.11 Her family history supports this possibility. One of his aunts was lobotomised for ‘bad nerves’. Two others, whose mental states apparently deteriorated during the London Blitz, had episodes of psychosis.12 Perhaps attesting to his mother’s memory of these events, Bowie once recalled the terror that engulfed the two of them during the Cuban missile crisis. ‘We’ve created such a terrible set of potential scenarios for the destruction of everything that we hold dear and love,’ he said. ‘I remember the Cuban [missile] crisis when I was a kid and how it upset my mother, and Dad would come and console her. I was terrified, really terrified.’13

Whatever the truth of his family’s mental states may have been, it seems that these early experiences left a lasting impression on Bowie’s psyche. In the 1970s he described his art and mind with phrases like ‘psychotic,’ ‘schizophrenic,’ ‘bipolar’ and ‘manic depressi[ve].’14 Like others with troubled childhoods, Bowie was also deeply narcissistic.15 Ex-girlfriend Dana Gillespie said that David ‘loved himself extremely.’ Meanwhile biographer Paul Trynka counted Bowie among ‘the most committed narcissists’ in 1960s London.16 Bowie also tended to choose lovers that resembled him. Hermione Farthingale was a ‘feather-cut Echo’ to Bowie’s ‘glam Narcissus’ in one journalist’s words.17 Angie Barnett’s looks mirrored his too, a woman he proposed to with a narcissistic caveat. ‘Can you handle the fact that I don’t love you?’18 Such lovelessness was sadly part of Bowie’s constitution. ‘Love can’t get quite in my way,’ he once said. ‘I shelter myself from it incredibly.’19 Elsewhere, he admitted: ‘Never have been in love, to speak of. I was in love once, maybe, and it was an awful experience. It rotted me, drained me, and it was a disease. Hateful thing, it was.’20

Bowie’s narcissism was legendary. Yet it masks his even deeper schizoid traits. An extremely sensitive man, Bowie also felt he was a ‘very cold person.’21 Lively onstage and in character, offstage he felt robotic, fragmented and disconnected from reality.22 The schizoid character, R. D. Laing says, insulates themselves from both reality and feeling to protect their fragile sense of self from collapse. Their defence inevitably harms them, though. It opens a vacuum within. The self then becomes a ‘bottomless pit’ within the schizoid man. A ‘chaotic nonentity’ or ‘a gaping maw that can never be filled up.’ A ‘restless nothing,’ in other words, ‘shaped by our fear,’ our ‘fearful sickness unto death.’23

At the Odeon Theatre that night in 1973—a place later called the Apollo but which should have been named Dionysus—Bowie killed Ziggy. Stagnation being ‘evil’ to him and capitalism, the persona had exhausted its potential. Even this homo superior had ‘outgrown its use.’24 In our post-cultural society ruled by creative destruction, Ziggy’s death was an act of survival for Bowie. Yet when Bowie symbolically sacrificed the character that had subsumed his identity, when he tore at his body and demolished his dressing room, he showed us that trauma, violence, and self-aggression were inseparable from destructive self-revolution. Bowie’s instability may have contributed to the success of his particular art. His art undoubtedly exacerbated it too.

‘We’re nothing / And nothing can help us.’

—David Bowie, “Heroes.”References

Buckley, D. (1999) Strange Fascination: David Bowie – The Definitive Story. London, Virgin Books.

Buckley, D. (2015) David Bowie: The Music and the Changes. London, Omnibus Press.

Critchley, S. (2014). Bowie. London, OR Books.

Critchley, S. (2016) On Bowie. London, Serpent’s Tail.

Devereux, E., Dillane, A., & Power, M. J. (eds.) (2015) David Bowie: Critical Perspectives. New York, Routledge.

Doggett, P. (2011) The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. London, The Bodley Head.

Fairbairn, R. (1994) Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality. London, Routledge.

Laing, R. D. (2010) The Divided Self. England, Penguin Classics.

Morley, P. (2016) The Age of Bowie: How David Bowie Made a World of Difference. London, Simon & Schuster.

O’Leary, C. (2015) Rebel Rebel. Winchester, United Kingdom, Zer0 Books.

Sandford, C. (1997) Bowie: Loving the Alien. London, Warner.

Schumpeter, J. A. (2003) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London, Routledge.

Steiner, G. (1971) In Bluebeard’s Castle: Some Notes Towards the Re-definition of Culture. New Haven, CT, Yale University Press.

Trynka, P. (2012) Starman: David Bowie – The Definitive Biography. Great Britain, Sphere.

Footnotes

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, p.83.

In Bluebeard’s Castle, chapter 3. See also https://www.nypl.org/blog/2016/01/11/david-bowies-top-100-books.

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, p.83.

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, p.84.

The Age of Bowie, p.279.

https://www.theuncool.com/journalism/david-bowie-playboy-magazine/, The Age of Bowie, p.309, and David Bowie: Critical Perspectives, p.115.

On Bowie, p.102.

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, p.82.

On Bowie, pp.102, 157.

https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/david-bowie-how-ziggy-stardust-fell-to-earth-183340/

http://www.rebeccaf.com/id/david-bowie-the-art-of.html

Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.14.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/david-bowie-on-911-and-god?ref=scroll

‘I’m really quite bipolar,’ Bowie once said, ‘and the depressed times, when everything felt like night, sometimes you get to such a low point that you physically beat at it until it bleeds – as you would say – bleeds till sunshine.’ See also https://www.moredarkthanshark.org/eno_int_uncut-apr01.html, https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/02/nazism-and-narcissism-david-bowie-flirtation-with-fascism.html and ‘David Bowie - Cracked Actor Documentary, HD, Part 2’ at 14:20.

Reflecting both his narcissistic and schizoid traits, Bowie apparently believed that he was part of a group he called ‘the Light People – extraterrestrials from some other planet or dimension in whose ranks [he] counted Leonardo, Galileo, Newton, Gandhi, Churchill and, closer to home, Dylan, Lennon and Hendrix.’ See Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.70.

Other early associates suggest—unkindly and queerphobically—that even Bowie’s bisexuality was a product of his narcissistic ambition. Though he slept with men, ‘what he really was was a narcissist’ who was indifferent to his partners, said former manager Tony Zanetta, while ex-bandmate Dick James felt that Bowie would flirt with anyone for personal gain, no matter their sex or gender. Biographer David Buckley also notes Bowie’s narcissism and self-absorption on pp.173-174 of Strange Fascination.See Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.32 and Starman, chapters 3 and 9.

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/feb/09/david-bowie-finding-fame-review

Starman, ch.7. See also Bowie: Loving the Alien, pp.48 & 65.

https://www.theuncool.com/journalism/david-bowie-playboy-magazine/

Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.105.

Fairbairn once observed that schizoid personalities tend to ‘play roles’ or ‘act parts.’ Doing so, the ‘schizoid individual is often able to express quite a lot of feeling and to make what appear to be quite impressive social contacts; but, in doing so, he is really giving nothing and losing nothing, because, since he is only playing a part, his own personality is not involved.’ Bowie exemplified this behaviour. He once said: ‘Offstage I’m a robot... Onstage I achieve emotion. It’s probably why I prefer dressing up as Ziggy to being David.’ Meanwhile Paul Morley wrote that ‘in the real world, outside of a distinct frame, he was acting all the time. He was acting himself again and again. He was acting all the time to make up for some deficiency in his sense of himself.’ See Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality, p.16, The Age of Bowie, p.287, http://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/mwfte.html, The Man Who Sold the World, p.239, and Rebel Rebel, p.408.

See The Divided Self, pp.145 & 162, and Bowie, p.179. Note as well that, by his own admission, his narcissistic need for fame also fuelled this productive instability. ‘Why [was] I doing any of these things?’ he said of his early restlessness. ‘It [was] because I wanted to be well-known.’ And elsewhere: ‘I felt far too insignificant as just another person... I want to be a supersuperbeing.’ See 43:25 of the Finding Fame documentary and his interview in Playboy, September 1976.

David Bowie: Critical Perspectives, p.114, and David Bowie: The Music & The Changes, p.40.