‘About two years ago, I realised I had become a total product of my concept character Ziggy Stardust. So I set out on a very successful crusade to re-establish my own identity. I stripped myself down and took myself apart, layer by layer.’

—David Bowie.1

To survive by suicide can only exact a heavy psychic price. In 1973, Bowie had discarded looks and personas before. Yet he had never discarded an identity as all-consuming as Ziggy. Predictably, the sacrifice unmoored him. In its wake there followed a period of confusion, instability and psychological disintegration.

For a time, Bowie’s transformation stalled. Trapped between the liberal, individualistic self he destroyed and the future to come, he first recorded Diamond Dogs. Another Kubrick-inspired album of glam rock, nihilism and ‘apocalyptic decay,’ a superficial variation of the Ziggy persona adorned the record’s sleeve.2 Later that year a Ziggy-themed TV special aired. Bowie also told William S. Burroughs of his plans for a Ziggy Stardust stage show. He toured Diamond Dogs, too, performing with an elaborate set based on the record’s themes.3 In this time of dissolution and reformation, Bowie clung to what he had abandoned. Meanwhile the self-aggression he unleashed the night he killed Ziggy only grew. His cocaine and amphetamine habit evolved into an all-consuming addiction. In drug-fuelled bouts of insomnia Bowie would stay awake for days at a time, driving his identification with the capitalist work ethic to an extreme as he furiously produced art. Anorexia soon followed as the artist starved himself until he weighed just eighty pounds.4

Years later Bowie noted the suicidality latent in these habits. It was a time, he said, where he was ‘killing himself.’5

Midway through 1974, though, Bowie found a definitive escape from his Ziggy persona. Once again he destroyed himself to create. In a fit of inspiration he scrapped his elaborate set and channelled his band’s sound away from rock. New material rapidly followed. In early 1975 Bowie’s next album appeared – the plastic-soul record, Young Americans.

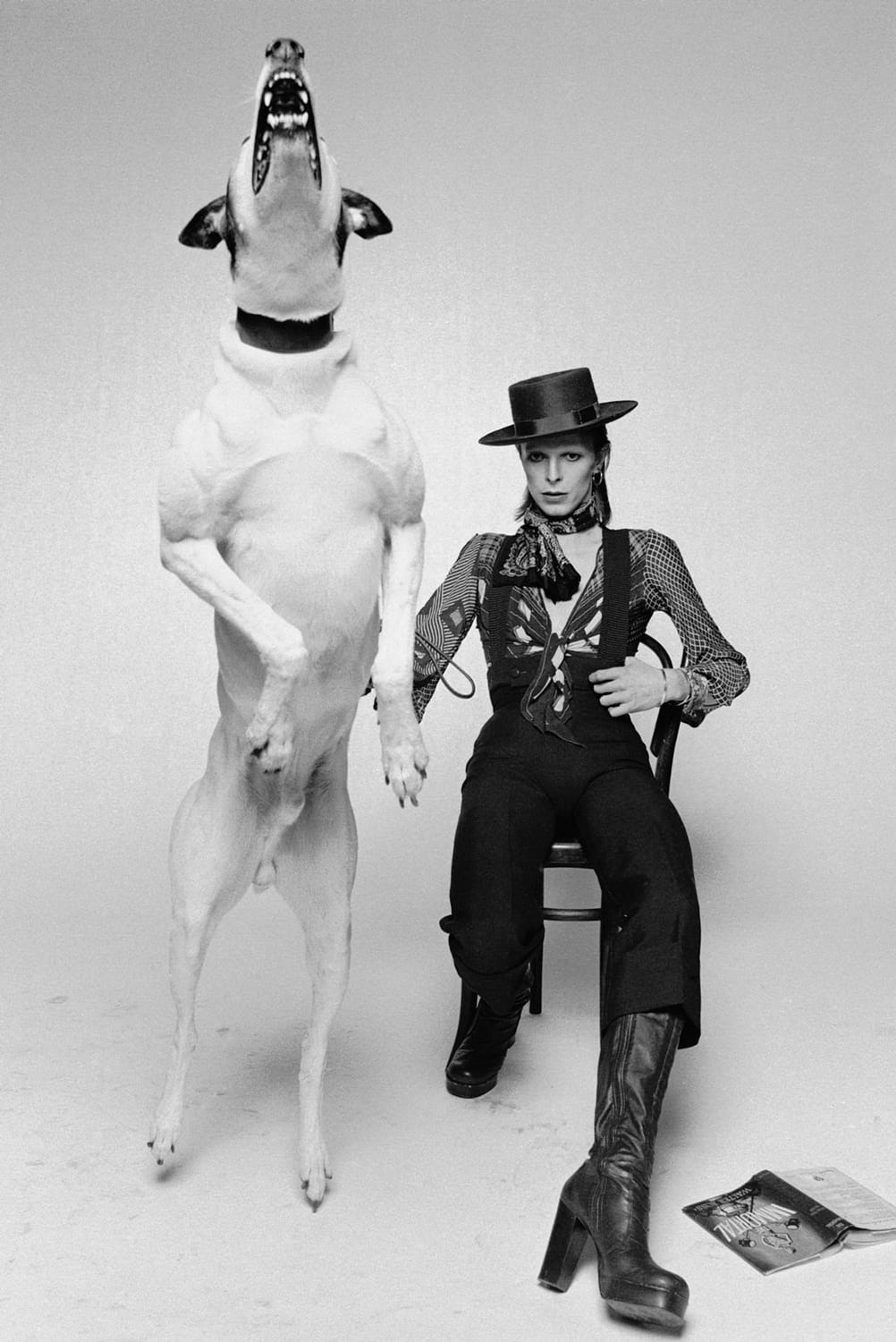

Nostalgia is a balm for anxiety. In his time of uncertainty, then, Bowie regressed and revived his passion for the American culture of his youth.6 According to Bowie, American soul was ‘kind of music [he’d] always wanted to sing.’7 ‘I wanted to be the baritone sax player in the Little Richard band,’ he later said of his childhood passions. ‘I probably also wanted to be Black at that particular time as well.’8 Reflecting this fixation, Young Americans was an optimistic sonic hybrid funk, soul and R&B. The LP’s sleeve represented ‘Bowie as a star in the “old Hollywood” tradition,’ too, and his new look took cues from James Dean and Philadelphia soul artists.9 Promotional shots deployed also Depression era iconography. In one photograph Bowie lay in front of the American flag, wrapped in a newspaper and resting his head on a pair of shoes. Another saw him in a bomber jacket and Converse gym boots, posed like the Statue of Liberty while valiantly brandishing a glass of milk—probably a reference to America’s Special Milk Program, which supplied ‘Victory Food’ to schoolchildren to fight malnutrition during WWII.

On Young Americans, Bowie finally departed from Ziggy’s post-cultural liberal individualism. In its place he became an archetype of the liberal politics that preceded Ziggy – that of Roosevelt, the New Deal, the Great Society programs and Keynesian economics. But Bowie’s identification with American culture was not based only on love or worship. It was also ironic and cynical.10 On the album’s title track, Bowie sings of the desperation, disappointment and failings of the American dream. Allusions to suicidality, the country’s issues of misogyny, racism, class disparities, materialism and liberal hypocrisy also haunt the song. On ‘Fame,’ he destroys the myths of the celebrity status he so desperately sought – a song that ironically became his first US number one single. Echoing Theodor Adorno, ‘Somebody Up There Likes Me’ also highlights the uncomfortable proximity between demagogues and popstars. The song says ‘"Watch out mate, Hitler's on his way back,"’ Bowie said in an interview. ‘[I]t's your rock and roll sociological bit.’11

At once a regressive embrace and excoriating criticism of his childhood ideals, Young Americans is an ambivalent record. Like America in the 1930s, where economic crisis forced the government to trade laissez-faire capitalism for regulated, New Deal liberalism, on Young Americans Bowie answered his liberal-capitalist identity crisis with a bid for stability. Fuelled by nostalgia for the same society Trump’s supporters fetishise, Bowie abandoned his anarchic, individualistic persona and identified with the liberal America he knew in his youth. Ultimately, though, Bowie found no refuge in these old ideals. Time had tainted them.

The 1970s were a time of frustration for the American Dream. The Bretton Woods system failed. Stagflation gripped the economy. Government policies failed to resolve the antagonisms of capitalism that led Bowie and the economy to crisis – the need for endless change, growth, and creative destruction. As Bowie toured Diamond Dogs and recorded Young Americans, the US weathered its second recession in five years. The stock market crashed. Oil prices and inflation rose. Instead of the American Dream, New Deal-style politics produced an anxious nightmare. They failed to deliver the ideal world they promised.

The myth of America sold to Bowie in his youth was disintegrating. His sense that things were ‘falling apart’ was undeniable; his nostalgia only heightened his sense of collapse.12 While he played at being American, then, Bowie’s drug addiction, anorexia and psychic anguish worsened. Two anecdotes reveal the depth of his ambivalence. On tour during this period, Bowie would watch recordings of his concerts after he finished playing. Guests in his hotel room ‘watched David enjoying himself on screen. His self-absorption was hypnotic.’13 Around the same time, Bowie also saw a TV screening of his final show as Ziggy Stardust. The gap between what he was and the emaciated and exhausted man he had become was undeniable. A fit of despair followed and Bowie tried to throw himself out his hotel window. Had he been alone, he may have succeeded in this suicide attempt.14

Beholden to the forces of creative destruction neither America nor Bowie could tolerate stagnation. Between their ideals of economic abundance, narcissistic self-actualisation and their fear of stasis, both country and artist had a need to become more than they were. But by the mid-70s neither could continue to promote the old myth of the American Dream. America soon answered this identity crisis with neoliberalism. But Bowie, perhaps because Ziggy taught him the traumas of unconstrained liberalism, chose another solution. Like the people of Germany’s Weimar Republic, where liberal politics failed to resolve the nation’s chronic uncertainty, instability, terror and disappointments, Bowie chose fascism.

References

Doggett, P. (2011) The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. London, The Bodley Head.

Morley, P. (2016) The Age of Bowie: How David Bowie Made a World of Difference. London, Simon & Schuster.

O’Leary, C. (2015) Rebel Rebel. Winchester, United Kingdom, Zer0 Books.

Sandford, C. (1997) Bowie: Loving the Alien. London, Warner.

Zanetta, T. & Edwards, H. (1986) Stardust: The Life and Times of David Bowie. London, Michael Joseph.

Footnotes

http://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/press/76-09-00-playboy.html

The Man Who Sold the World, p.201. Note that Ziggy also appeared on the sleeve for Pin-Ups, Bowie’s covers album recorded just before Diamond Dogs.

See The 1980 Floor Show and https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/beat-godfather-meets-glitter-mainman-william-burroughs-interviews-david-bowie-92508/

https://www.bowiebible.com/albums/station-to-station/3/#The_side_effects_of_the_cocaine

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/david-bowie-classic-very-sad-song/

One biographer notes that Bowie, aged 11, was ‘fascinated with guns and, not coincidentally, all things American.’ Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.23.

Paul Morley argues it was also the ‘calculatedly commercial Bowie response to achieving the American fame and glamour he had set his heart on.’ See Age of Bowie, p.322, and The Man Who Sold the World, p.214.

https://www.npr.org/2016/01/11/462653510/david-bowie-on-the-ziggy-stardust-years-we-were-creating-the-21st-century-in-197

Stardust, p.211.

This ambivalent attitude extended to Bowie’s descriptions of his record. In interviews for the record, he said it was the most personal record he had made since Space Oddity. Elsewhere, he described it as ‘plastic soul,’ or ‘the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey,’ and said it was ‘the phoniest R&B I’ve ever heard. If I ever got my hands on that record when I was growing up I would have cracked it over my knee.’

Rebel Rebel, p.360. See also The Man Who Sold the World, pp.221-222.

Stardust, p.227.

This echoes another anecdote from 1968 where, facing dire commercial and artistic prospects, he tried to jump out his window. ‘Terror-stricken, sobbing, he heaved a huge chair through the plate-glass window of his bedroom and nearly threw himself after it.’ See Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.45, and The Man Who Sold the World, p.219.