"A future we knew would never come to pass"

Chapter III, Part VII - The Return of the Thin White Duke

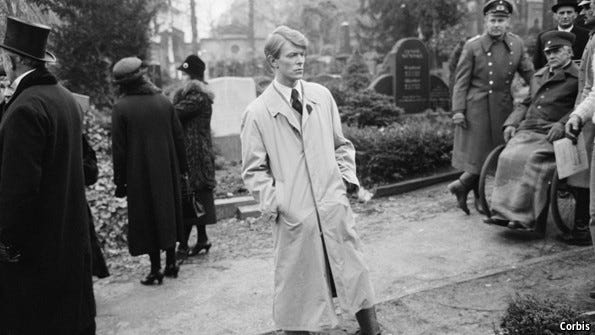

The approach of death birthed Bowie’s fascism. Intense though it was, his fixation died sometime in 1976. Its end came in several stages. First, Bowie blew his nose one day while living in California. To his horror, ‘half his brains came out’ onto the tissue.1 Confronted by the wreckage caused by his cocaine addiction, his unconscious death drive suddenly became conscious. ‘I really was killing myself,’ Bowie realised, ‘and I had to do something drastic to pull myself out of that.’2 To save himself from his suicidal impulses, he resolved to leave L.A. Departing America for Europe, he toured his new album across the continent and gave what would be his final interview on fascism in Stockholm. In April 1976, he then returned to the United Kingdom. The day after his London homecoming, NME published a photograph of Bowie apparently giving a Nazi salute in the back of a black Mercedes. Bowie said the photographer had merely caught him at the zenith of a wave. The public, however, were horrified.3

Publicly shamed for his fascism, Bowie soon moved to Berlin. His fascist interests already dwindling, there he met young Germans ‘whose fathers had actually been SS men.’ A Nazi fanatic who lived in his building also invited Bowie to view his replicas of the skulls of Hitler’s cabinet and lectured him on the ‘dental merits of “Nordic blood.”’4 Encountering the real consequences of Hitler’s violence, Bowie’s fascination almost instantly collapsed.

Bowie’s fascism withered in Berlin. The Thin White Duke died. As he did at the Odeon Theatre, Bowie then destroyed his persona once again. Yet now he neither reached for greater fame. Nor did he descend into addiction. Instead he retreated from public life to heal. Alongside Tony Visconti and Brian Eno, he then recorded some of the best music of his career – Low, “Heroes” and Lodger. ‘For whatever reason, for whatever confluence of circumstances,’ Bowie once said of these records, ‘Tony, Brian and I created a powerful, anguished, sometimes euphoric language of sounds. In some ways, sadly, they really captured, unlike anything else in that time, a sense of yearning for a future that we all knew would never come to pass.’5

In the wake of his fascism, Bowie used music to return to reality. With sound he mourned his lost futures. The music he made was fragmentary. Often it was wordless. We don’t know exactly what private sadness Bowie articulated in sound. Perhaps he grieved for the Duke’s utopia of total certainty, Ziggy’s messianic dream of freedom unbound. Maybe he cried for some part of his past he projected onto the tomorrows he hoped might come. He may have mourned whatever it was that opened the ‘restless nothing’ in his heart. Whatever Bowie grieved, though, the experience changed him. His time in Berlin made him a more stable man. He never praised fascism again.

For the rest of his life, Bowie distanced himself from the comments he made as the Thin White Duke. ‘The only thing I can now counter with is to state that I am NOT a fascist,’ he once said. ‘I'm apolitical.’6 Despite his political disinterest, Bowie eventually became a vocal supporter of mainstream left-liberal politics after he left Berlin. He played charity events and spoke out against racism. In the 1990s he voiced his support for Tony Blair.7 Signalling his support for late 20th-century capitalism, he even issued his own financial instruments – Bowie Bonds. Bowie ended his fascist fixation, then, with that ‘new form of liberalism’ he craved. This time, though, it was neoliberalism.

References

Rüther, T. (2014) Heroes: David Bowie and Berlin. London, Reaktion Books.

Sandford, C. (1997) Bowie: Loving the Alien. London, Warner.

Footnotes

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/interviews/david-bowie-25-years-ago-done-just-everything-possible-do/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/interviews/david-bowie-25-years-ago-done-just-everything-possible-do/

Christopher Sandford disputes Bowie’s defence here, claiming that many correspondents of Britain’s national press ‘had been at Victoria to see that his gesture was neither a “peace sign” nor a “trick of the light” as he claimed.’ On May 8th, 1976, a few days after this photo was published, NME’s Max Bell also claimed that Bowie gave another Nazi salute at a concert. See Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.157, https://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/1976.html, and http://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/press/77-10-29-melody-maker.html

Heroes: David Bowie & Berlin, p.101, and Bowie: Loving the Alien p.178.

https://bowiesongs.wordpress.com/2011/05/11/heroes/

http://www.bowiegoldenyears.com/press/77-10-29-melody-maker.html

Bowie: Loving the Alien, p.330