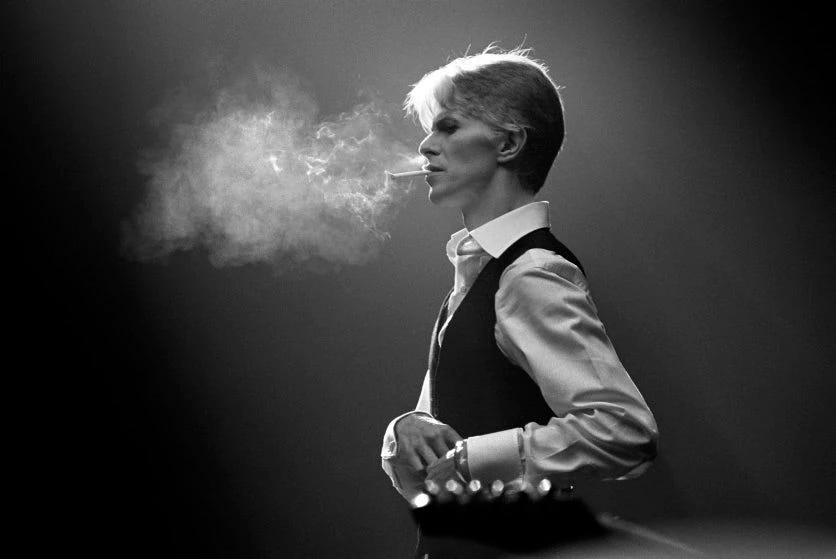

‘People look to me to see what the spirit of the Seventies is.’

‘With our makeup and funny clothes… we’re only heralding something even darker than ourselves.’

—David Bowie.1

In the 1970s, David Bowie deployed his talent and narcissism to pursue the ideals of liberal, individualistic post-culture. But the psychological stresses that came with his success in the creative-destructive world of liberal capitalism led to an identity crisis. After he killed Ziggy he became suicidal, anorexic and dependent on drugs. In response to this crisis, Bowie first sought refuge in a nostalgic identification with the liberal ideals of past decades. When this failed, he became transfixed by Hitler’s narcissism. He began to think of himself as a supreme political leader. The certainties of fascism became appealing.

Later in life, Bowie claimed that his interviews as the Thin White Duke were all given ‘in character.’ Elsewhere—and convincing absolutely nobody—he said that the Duke was a ‘caricature’ he made to fight fascism.2 It’s a shame Bowie was not more forthright about his intentions as the Thin White Duke. For when Bowie became a fascist as he tried to portray the truth of his time, he revealed something once articulated by philosopher Alain Badiou.

In his 1977 article ‘The Fascism of the Potato,’ Alain Badiou accused fellow philosopher Gilles Deleuze of proto-fascist tendencies.3 Deleuze, like Bowie, was an avid reader of Nietzsche. And like Ziggy, Deleuze believed that our politics should be anarchic, multiple and unconstrained by judgements.4 Deleuze thought identity was a fiction and wanted us to fluctuate freely.

Many on the left adopted Deleuze’s vision as their own. Michel Foucault even proclaimed it a properly anti-fascist politics – his work was an ‘Introduction to the Non-Fascist Life.’5 Badiou, however, was not convinced. Deleuze’s vision certainly seemed liberating. It tried to be anti-fascist. Yet Badiou believed Deleuze’s philosophy really laid the ground for fascism. ‘At the far end of [Deleuze’s] Multiple,’ he writes, there is the ‘fascist despot.’6 In his article, Badiou argued that the masses can resist fascist dictatorship only if they have a unity of their own. When the masses are divided and ‘multiple’ a fascist ‘dictatorship’ can organise them from without.7 The ‘One’ of the authoritarian state both ‘maintains the people as multiple’ and organises that multiple for its own ends, says Badiou.8 The tyrant can only be resisted, then, if the masses choose unity over the anarchy. They must refute the division of difference.

Fascist leaders need the masses to be unstructured and isolated if they are to win power. They otherwise cannot present themselves as a unifying force that can realign the terrified people toward their single, glorious goal. The fascist fantasy of ‘authentic community’ and ‘social solidarity’ has no appeal if we stand together already. Deleuze’s anarchy, then, can only pave the way for fascism. Instead of liberation, unrestrained freedom can deliver us to tyranny. Terror, isolation and disintegration links liberalism to fascism. Fear, loneliness and falling apart – these are the ante-fascist’s truest feelings. They are also the emotions of a man who wanted to be regarded as an ‘individualist.’

Throughout his career, David Bowie maintained his identity with the logic of creative destruction. Endlessly evolving his sound, Bowie knew that to create and grow you must destroy whatever wealth already exists. But when he gave his whole body and self over to his art in the 1970s he showed that Badiou’s social connection between liberalism and fascism exists in the mind, too. A canvas on which he painted the truth of his time, Bowie’s life and mind mirror the dynamics of liberal, capitalist societies in crisis. Between Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke, we also see how the instability of liberal, capitalist economies undermines the individual’s sense of self, heightening their narcissistic grandiosity and creating a countervailing need for stability, omnipotence and certainty. We also see that fascism can answer this need. That order emerges to negate chaos. That liberal capitalism can produce the conditions in which fascism thrives.

The Thin White Duke is the dark underside of Ziggy Stardust. The series of identifications that connect these characters—from Schumpeterian capitalism, to Keynesianism, and finally to fascism—represents both an increasing bid for order and a path of possible responses to failed market capitalism. Like the German nation itself, Bowie also returned to liberalism after his period of fascism. The Germans became liberal again because the Allies annihilated them in the war. Yet Bowie did not need to be destroyed to free himself of his fascism. Though it took an encounter with the death he unconsciously sought and an intensely creative work of grief for his futures lost, he retreated from the fascist abyss. Even at the very limit of fascism, Bowie shows us, we can still trace a path back to safety.

Sadness and the lucid confrontation with death. Perhaps it is here that we might find some hope.

References

Badiou, A. (2012) The Adventure of French Philosophy. London, Verso.

Deleuze, G. (1994) Difference & Repetition. New York, NY, Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. (1998) Essays Critical and Clinical. London, Verso.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983) Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, MN, University of Minneapolis Press.

Reynolds, S. (2016) Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and its Legacy. London, Faber & Faber.

Žižek, S. (2012) Organs Without Bodies: On Deleuze and Consequences. London, Routledge Classics.

Footnotes

Shock & Awe: Glam Rock & Its Legacy, p.550, and https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/beat-godfather-meets-glitter-mainman-william-burroughs-interviews-david-bowie-92508/.

The Man Who Sold the World, p.256.

‘The Fascism of the Potato,’ p.201, in The Adventure of French Philosophy. See also Organs Without Bodies by Slavoj Žižek.

See Difference & Repetition, Anti-Oedipus and ‘To Have Done With Judgement’ in Essays Critical and Clinical.

Anti-Oedipus, p.xiii.

The Adventure of French Philosophy, p.193.

The Adventure of French Philosophy, p.200.

The Adventure of French Philosophy, p.200.