Keynes & Economic Crisis

Chapter IV, Part II - The Road to Serfdom

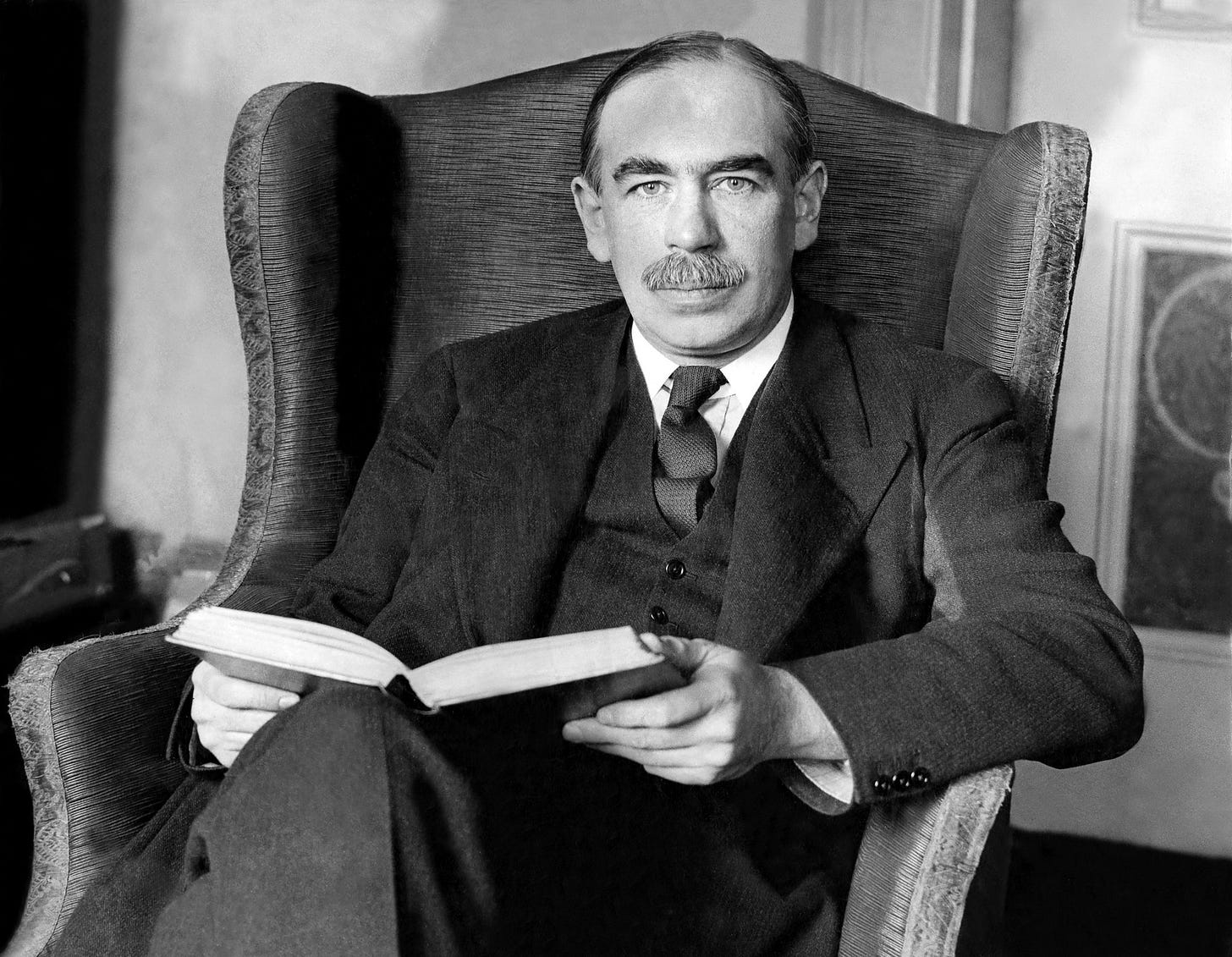

In the years and decades after the Great Depression, economic policy around the world was profoundly indebted to the thoughts of one man—John Maynard Keynes.

Keynes was an English economist based at Cambridge University, and he gained international renown in 1936 with the publication of his book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money. The book was Keynes’ attempt to reformulate economic theory which, at the time, had no meaningful way of explaining or remedying the Great Depression.

At the time, Keynes’ ideas were completely unconventional. Yet as Keynes wrote to his friend, George Bernard Shaw:

I believe myself to be writing a book on economic theory which will largely revolutionize — not I suppose, at once but in the course of the next ten years — the way the world thinks about its economic problems. I can't expect you, or anyone else, to believe this at the present stage. But for myself I don't merely hope what I say,— in my own mind, I'm quite sure.

History proved Keynes correct. Departing radically from all economists that came before him, Keynes realised that economic crises became prolonged depressions because of their effects upon collective business confidence and investment behaviour. When economic growth recedes, unemployment rises and incomes fall; in this situation, he argued, investors losing money today become less sure of the future profitability of their investments. Unsure whether there will be demand for the products they produce, they therefore reduce their spending, preferring to save their money for a safer, future date.

Such behaviour is rational for the individual. However, it is catastrophic in aggregate. For if all investors reduce their spending, fewer jobs are created in an economy; incomes fall; people spend less money; today’s investments become less profitable; and so future investments are discouraged. In times of economic crisis, a vicious cycle begins: the investors’ behaviours inevitably create the situation they feared. Their anxieties proven to be correct, they withdraw even further from the market, exacerbating the downturn in investment and deepening the economic crisis ad nauseam. The vicious cycle cannot be stopped without a reversal of the loss of confidence; but the loss of confidence cannot be reversed while the cycle persists.

For these reasons, Keynes believed that economies fall into prolonged depressions when an overall mood of pessimism prevails. Hence, he said, it is the government’s job to counteract these depressed, pessimistic moments with spending that boosts our confidence in the future of our economies. When crises occur, the government should not cut spending, then. Rather, they should expand their spending, supporting jobs, incomes and consumer demand, thus enticing individuals to invest their money and produce economic growth. In Keynes’ eyes, crises were exactly the moments when governments should invest in large, ambitious projects, from welfare and mass education to technology investment and infrastructure expansion. For only this could stop our economies from collapsing during moments of despair.

Keynes’s theories of government spending were partly based in his acute recognition of human fallibility. In The General Theory, Keynes argued that our economic decisions could never be truly rational. When we buy financial assets, he said, we always do so with an expectation that their price will change in the future; the price we pay today is based on our estimates of what these changes will be. But because no human knows what the future will bring, by necessity our estimates can never be completely accurate - hence, we can never know the true or ‘correct’ price to pay in the present. People make guesses, not according to their rational calculations, but with what Keynes called their ‘animal spirits’—their spontaneous, irrational feelings of optimism and pessimism that derive from self-referential and unstable beliefs about what others think the general masses of people believe will happen. ‘Human decisions affecting the future,’ Keynes wrote, ‘cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation, since the basis for making such calculations does not exist.’ Not knowing the future, we inevitably rely on ‘whim or sentiment or chance’ to make our choices.1

Unlike any economist before him, Keynes saw that humans are fallible, emotional, ignorant and irrational creatures. He also saw that economic individualism does not work en masse—that, if capitalism is to survive, it requires governments to partly socialize individual investment. Keynes certainly appreciated the novelty of his theory. Yet even he never could have foreseen how his arguments would shape the course of world history.

References

Keynes, J. M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Footnotes

The General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money, ch 12.