In the years after Keynes published The General Theory, his ideas became highly influential. Governments struggling to recover from the Depression adopted his ideas in haste. Policies like Roosevelt’s New Deal exemplified the Keynesian approach. War spending, too, required soon after Keynes published his book, likewise had the desired effect on economic growth. Both fascism and the fight against it dragged the world economy out of its depressive slump. Capitalism survived, but at the price of utter carnage.

By 1944, Keynes was an economist of immense stature. President Roosevelt invited him to a conference held in New Hampshire’s Bretton Woods where delegates from Allied countries came together to plan the post-war world order.1 Here, world leaders developed an international framework that would ensure stability and prosperity once the war had ended. Institutions that still exist—the IMF and the World Bank—were born at this meeting, each designed to provide emergency financial assistance and development funding for countries around the world. A system of fixed exchange rates and strict capital controls known as the Bretton Woods system was also established. Under this system, countries included in it would peg the value of their currency to the US dollar. And the dollar’s value would be tied to gold held by the US government—$35 USD could be exchanged for an ounce of gold.

Bretton Woods was to be the ground of the post-war world order. And at the meeting, Keynes voiced his support for this system of fixed exchange rates. Yet he also argued that the system would be inherently unstable without further measures. He saw that if the US was to run large deficits in either trade or government spending for too long, their currency would fall in value. Eventually, they would be unable to afford to exchange dollars for gold at the required rate, he said, and the system would implode.

Many of the attendees agreed with Keynes’ argument. Yet the US—who, relatively untouched by the war, was the most powerful country in the room—rejected his proposal. Historically, the imbalances Keynes warned against were essential for countries who wished to project hegemonic power around the world. And the US had a vision of the future where they dominated the world order—where they would act as the world’s exporter, sending goods overseas while using their profits to rebuild countries like Japan and Germany as centres of demand for their own products. To their peril, they rejected Keynes’ ideas. And so the Bretton Woods system came into effect lacking the balances that would constrain US power but ensure the system’s long-term sustainability.

After the war, the Bretton Woods system fostered a period of miraculously fast economic growth and rising prosperity. The US, whose activities then accounted for approximately a third of global output, used their profits to rebuild Japan and Germany as major centres of industry. With the Marshall Plan they helped to rebuild Europe, and with the onset of the Korean War, they lavished even more funds upon Asia. Germany and Japan soon became major exporters in their region; in turn, they used their own surpluses to buy exports from the United States, creating a demand for American goods that secured the US’s economic and political dominance.

At home, the US government indulged in large expansionary programs—the intercontinental ballistic missile program and the spending needed for the Korean War supported the country in the ‘50s. Later, Kennedy’s anti-poverty and pro-science New Frontier policies, Johnson’s Great Society Program, and the Space Race further supported industry, demand and economic stability. And just as in World War II, government spending on the Vietnam War and the GI Bill that paid for veterans’ university tuition boosted production and created jobs in the US.

These policies, of course, served a further ulterior aim. The Cold War was truly underway the moment the Soviet Union detonated their first atomic bomb in 1947. Once they had a nuclear rival, the US could no longer use ‘hard’ military power to dominate world affairs. Instead they used a combination of proxy wars and ‘soft power’ to display their supremacy over the Soviet Union. All these policies—whether they supported technology, culture, education, poverty reduction, economic growth, infrastructure, or war in foreign countries—shared the tacit aim of establishing American dominance in the post-nuclear world. The bomb itself influenced the form they took—no longer war, but ‘war by other means,’ cultural, economic and political.2

Cold War spending had other unintended consequences, too. Consumption rose across with incomes and output, and the ecological exploitation of the planet increased in tandem. The spending on cutting-edge military technologies also led to the development of computers and the internet, while the US government’s support for education created a skilled population who could exploit these technologies at work. The result, eventually, would be the deindustrialisation of the country, and the rise in the digital technologies that manipulate and surveil us today. Discontent and paranoia—the shockwaves from Hiroshima shake us all in the most unexpected ways.

Naturally, these Keynesian-style programs that supported economic growth were enormously expensive for the US government. As they pursued these programs, the US government’s budget surplus rapidly became a budget deficit, financed by borrowing. At the same time that this deficit grew, America also slipped into trade deficits with the nations they helped to reconstruct—Japan and Germany. After less than thirty years, then, the US budget and trade surpluses that sustained the Bretton Woods system had vanished. Just as Keynes had foretold, the exchange rate system had fallen into peril. Ironically, it was because the US pursued the Keynesian-style policies he recommended that the system was failing.

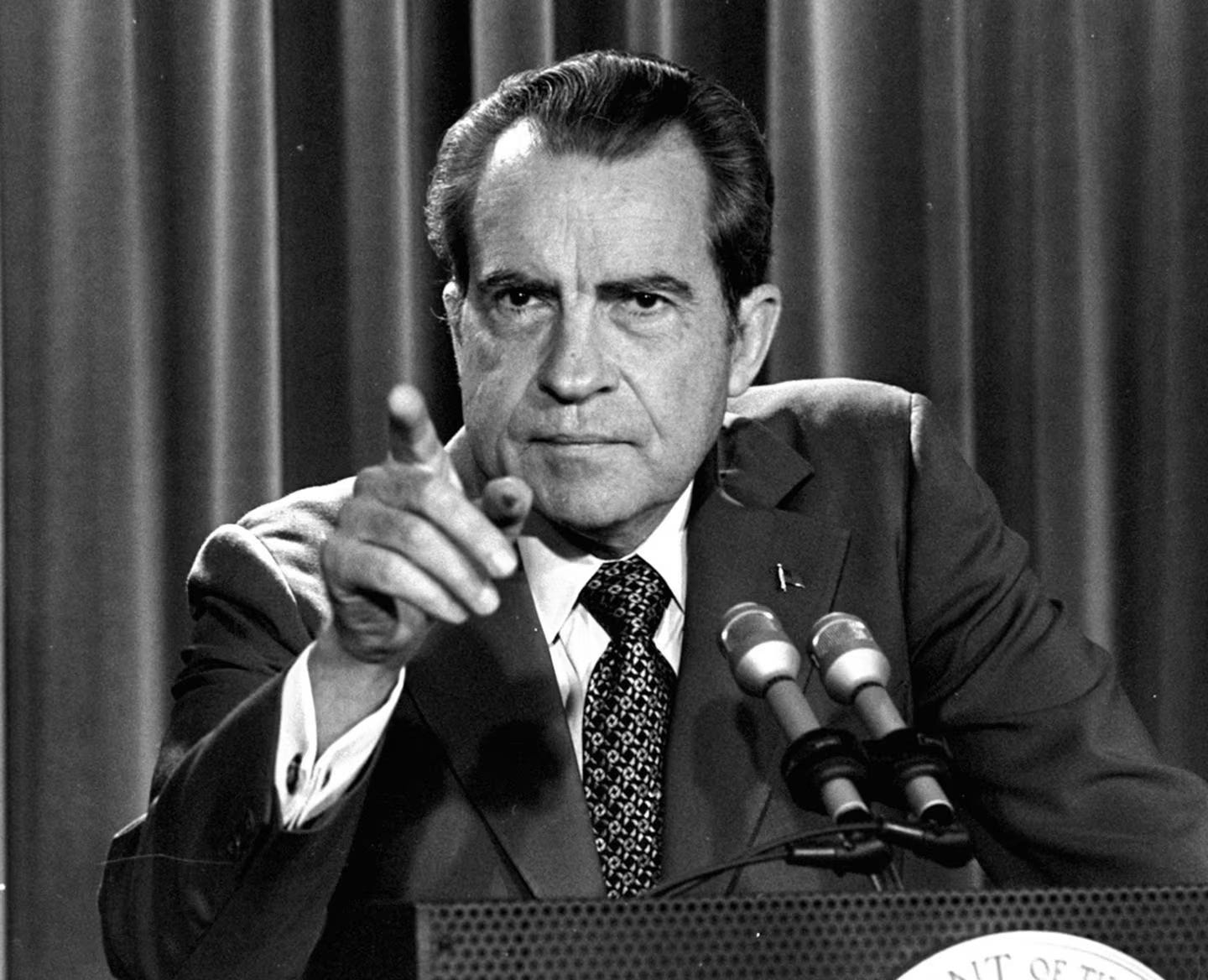

In late 1971, America’s financial imbalances finally proved too much for the fragile Bretton Woods system. Following a collapse in countries’ confidence that the US could continue to exchange dollars for gold at the fixed rate, President Nixon announced on August 14th that he would suspend the gold guarantee. Afterwards, the Bretton Woods system was effectively dead. The ground of the post-world order collapsed. And in its place, the world established a system of floating exchange rates, where values could oscillate freely, determined by the laws of demand and supply.

Another indirect consequence of the bomb, then—where our currencies were once grounded in gold, they became groundless too, their values determined by nothing more than the forces of desire and violence.

‘For Fire, everything is an exchange and Fire for everything, just as for gold, money and for money, gold.’

—Heraclitus.

References

Nye, J. S. (1990) Soft Power. Foreign Policy, 80. pp.153-171.

Varoufakis, Y. (2015) The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the World Economy. London, Zed Books.

Footnotes

Much of the following account of the Bretton Woods system was drawn from Chapters 3 and 4 of Yanis Varoufakis’ book, The Global Minotaur.

See Joseph Nye’s article, ‘Soft Power.’