The Mont Pèlerin Society, which still exists and meets as of 2023, counts Nobel laureate economists Milton Friedman, James Buchanan and Gary Becker, as well as famed philosopher Karl Popper, among its past members. In the decades after its founding, a highly influential ‘thought collective’ emerged from those early meetings in 1948. Its members ascended to positions of power in academic departments—namely, the University of Chicago Law School, the faculty where Barack Obama lectured before he became president, and the London School of Economics—think tanks like the Institute of Economic Affairs and the American Enterprise Institute, as well as philanthropic foundations like the Volker Fund. Together these institutions sought to re-educate the world’s populace on the meaning and values of political life.1 Their ideas would eventually reach the most exclusive halls of power around the world—the Oval Office, Downing St, the Bundestag, and more.

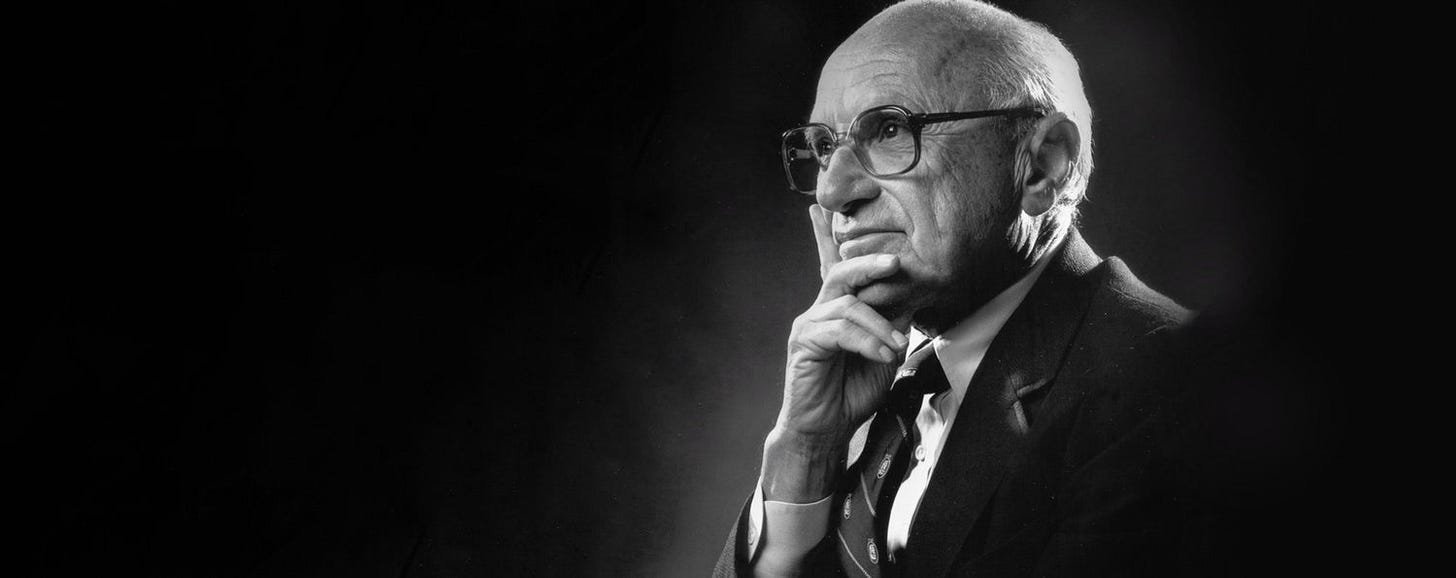

The University of Chicago’s Economics Department was especially influential in promoting the neoliberal doctrine. Chicago School professors and students, Friedman, Buchanan and Gary Becker among them, spent decades developing and articulating a radically different vision of individuals and their societies to that held by Keynes. In 1951, Friedman published an article called ‘Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects,’2 where he made unconstrained competition in free markets both the supreme mode of individual freedom, and the paramount defence against state interference, totalitarianism and exploitation. He also argued for a strong state that would administer that market, and a minimal welfare system that provided for the poor on the condition that it did not interfere with competitive markets.

Friedman would eventually distance himself from the word, ‘neoliberalism.’ His thought, however, adhered to its tenets throughout his life. In his later book, Capitalism & Freedom, he said that minimum wage rates, detailed regulation of banking, social security programs and public housing were unjustifiable and illiberal.3 He proposed a system of floating exchange rates that would enable free trade and railed against fixed exchange rate systems like Bretton Woods that inhibit trade and capital flows, and which he saw as the ‘most effective way to convert a market democracy into an authoritarian economic society.’4 Elsewhere he called the idea of corporate social responsibility ‘subversive,’ arguing that a corporation’s only obligation should be to maximise shareholder profit.5 He reiterated his idea that Central Banks represented an undesirable and irresponsible concentration of power, and whose control over the supply of money was the primary cause of inflation.6 And, echoing Hayek, he warned readers against the dangers of democracy: ‘The fundamental threat to freedom is power to coerce, be it in the hands of a monarch, a dictator, an oligarchy, or a momentary majority.’7

While Friedman contributed neoliberal ideas to macroeconomic thinking, his colleague, Gary Becker, reformed economists’ views on human labour. Becker’s Nobel Prize-winning innovation was his recognition that people ‘invest in themselves’ through education and self-improvement; that they are therefore just like capitalists who invest in machines or equipment; and that we should regard ourselves as ‘human capitalists’, whose assets were our own minds and bodies, laden as they are with skills, achievements, ‘health’, and capacities for work. Becker’s vision was of man alienated from within himself, whose soul was commodified, who could and should exploit any aspect of his existence, be it mental health, relationships, or our perceptual experience, for economic gain. To quote Michel Foucault, Becker’s genius was to recast people as ‘ability-machines,’ whose aim in life was to become ‘capitalists of themselves’ and generate ‘psychic income’—that is, what we once called ‘enjoyment.’8

As Becker acknowledged in his Nobel Prize lecture, the Chicago School’s infamous view of human nature lay at the core of his economic theories. Unlike Keynes’ vision of humanity, which saw us as vulnerable creatures, constrained in our rationality by our ignorance of the future and by our ‘animal spirits,’ Chicago School economists believed that people were rational, utility-maximising economic actors whose sole aim was the satisfaction of their known, ordered preferences. They viewed human behaviour in a strictly means-ends fashion, whose actions were all dedicated to self-centred utility maximisation—no matter how altruistic or self-sacrificing those actions were.

In neoliberal ideology, man was fundamentally concerned with himself. Nobel laureate economist James Buchanan—a man who believed public higher education generated ‘too much democracy’—restated this principle rather poetically in his Limits of Liberty.9 'In a strictly personalized sense,’ he writes, ‘any person’s ideal situation is one that allows him full freedom of action and inhibits the behavior of others so as to force adherence to his own desires. That is to say, each person seeks mastery over a world of slaves.’10 This is the vision of man at the heart of economic theory today. Where Keynes’ irrational, agnostic once stood, there is now a psychopathic narcissist—a slaver at the centre of neoliberal thought.

References

Cannon, A. (forthcoming) Once Death is God: Kanye, Bowie & the Allure of Fascism.

Brown, W. (2019) In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. New York, Columbia University Press.

Buchanan, J. (2000) The Collected Works of James Buchanan, Volume 7: The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan. Indianapolis, IN, Liberty Fund.

Friedman, M. (2002) Capitalsm & Freedom. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Mirowski, P, & Plehwe, D. (eds.) (2015) The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Footnotes

The Road from Mont Pelerin, pp.430-431.

https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/214957/full

Capitalism & Freedom, pp.35-36, 54.

Capitalism & Freedom, p.57.

Capitalism & Freedom, p.133.

Capitalism & Freedom, p.54.

Capitalism & Freedom, p.16.

C.f. Once Death is God: Kanye, Bowie & the Allure of Fascism, ch 3.

In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, p.62.

Collected Works, vol. 7. The Limits of Liberty, p.117.