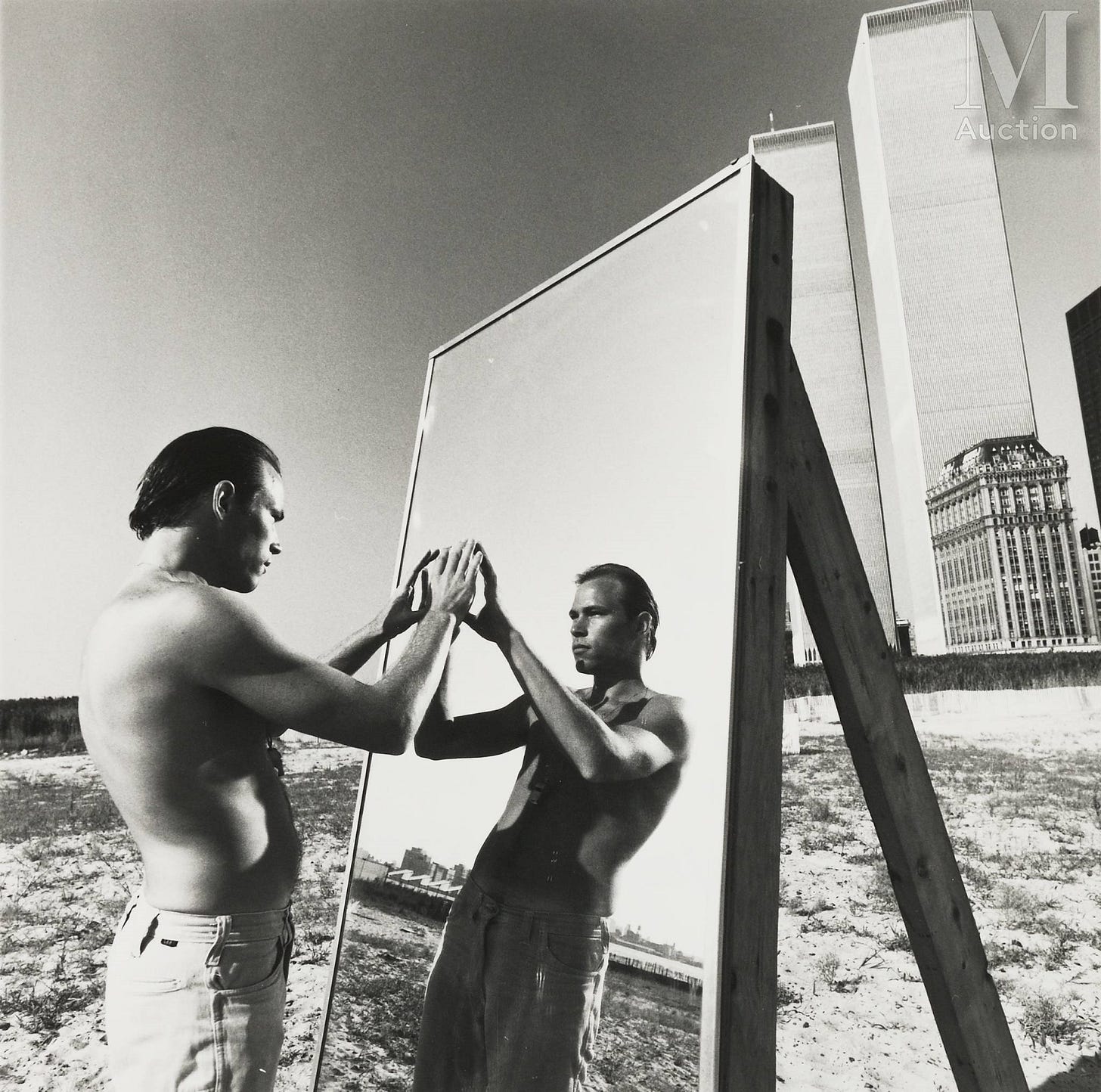

Following the efforts of neoliberal economists like Friedman and Becker, an intellectual edifice arose that justified Hayek’s vision of a free society where everything was subject to the economic principles of market competition and personal utility-maximisation. Where, to quote Slavoj Žižek we ‘are free to do anything as long as it involves shopping.’1 Where the welfare state was stripped back and the responsibility for survival was transferred back to families and individuals. Where we were equally free to be entrepreneurs of ourselves with our own portfolios of self-investments, or to starve on the streets, entitled to nothing if we do not work.2 Where democracy was discarded and ‘“freedom” was recoded to mean only the capacity for self-realization attained through individual striving for... wants and desires.’3 Where our ideals were no longer social projects like Pruitt-Igoe, but the grandeur of private wealth and power represented by the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers, those two monoliths doubling and reflecting one another into infinity—Narcissus and Echo on the New York skyline.

President Nixon’s decision to suspend the gold-standard in 1971 marked the moment when economists and policymakers turned away from Keynesian ideas and towards Hayek, Friedman and Becker’s neoliberalism. A man named Paul Volcker, whom Nixon appointed as a key economic advisor in 1970, was partly responsible for the change. Reporting to Henry Kissinger, Volcker wrote a report that encouraged the government to suspend the gold standard, a suggestion they followed the next year.4 Volcker’s report to Nixon echoed Milton Friedman’s well-known desire that Bretton Woods be replaced with a system of floating exchange rates, where currency values were determined by pure, market forces.5 ‘Governmental control of the price of gold, no less than the control of· any other price, is inconsistent with a free economy,’ wrote Friedman in 1962.6 A decade later, that government control was no more.

Speeches and decisions Volcker made in later years are even more suggestive of the influence of Friedman’s neoliberal ideas. In 1978, following years of economic discontent and stagnation in the United States, Volcker gave an address at Warwick University where he outlined his vision for the world economy of the 1980s. Here, as the world faced its second oil crisis in under a decade, this one connected with the Iranian revolution, he made a remarkable comment: he said ‘a controlled disintegration of the world economy is a legitimate objective for the 1980s’.7 Volcker believed that fixed exchange rate regimes like Bretton Woods had left countries overly integrated with one another. Under such systems, governments were forced to tailor their domestic policies and their trade balances to meet the requirements of the exchange rate system: they lost political autonomy as a result. Volcker believed such restrictions were inappropriate for a world where technology had made the movement of goods, people and capital more liberal than ever before. And so he suggested that ‘disintegration’ would be a good thing for the world. It would allow political autonomy, he thought, as well as free capital flows and free movement between nations.

Once again, his thinking bears the imprint of neoliberal economics: this kind of liberalisation that enabled ‘complete free trade’ and ‘floating exchange rates’ is exactly what Friedman had called for nearly twenty years before.8

Shortly after this speech, President Carter made Volcker the Chair of the Federal Reserve—an institution for whom Minoru Yamasaki, architect of the World Trade Center, had designed two major offices in Detroit and Richmond. To combat the spiralling inflation at the time, Volcker followed the Friedman playbook once more. Instead of targeting oil prices, Volcker decided that the inflation was being caused by an oversupply of money in the US economy. So he promptly raised interest rates to 20%, smashing the inflation without addressing its source. The side-effects were predictable. The US soon entered a recession for the second time in a decade; unemployment surged, too, reaching 10.8% by the end of 1982.

With this economic shock, Volcker’s ‘controlled disintegration’ began. While his policies were disastrous for working class people, they created a perfect opening for neoliberal policies. The crisis smashed labour power and crippled the unions in the USA; so weakened, Ronald Reagan’s administration could enact its sweeping reforms of labour regulationa, corporate power and the welfare state without resistance. With the Volcker shock, then, America’s neoliberal era truly began. And far from securing itself against those political outcomes Hayek, Friedman and others deplored, the country began its passage down the road to serfdom that has led to the ante-fascism of today.

References

Brown, W. (2019) In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. New York, Columbia University Press.

Mirowski, P., & Plehwe, D. (eds.) (2015) The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

Varoufakis, Y. (2015) The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the World Economy. London, Zed Books.

Volcker, P. (1978) The Political Economy of the Dollar. Available at: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/quarterly_review/1978v3/v3n4article1.pdf

Footnotes

The Road from Mont Pelerin, p.421.

In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, pp.20 & 38.

The Road from Mont Pelerin, pp.161-162.

The Global Minotaur, p.94.

Capitalism & Freedom, pp.61-64, 69-70.

Capitalism & Freedom, p.59.

The Global Minotaur, p.100. See also ‘The Political Economy of the Dollar’.

Capitalism & Freedom, pp.71-74.