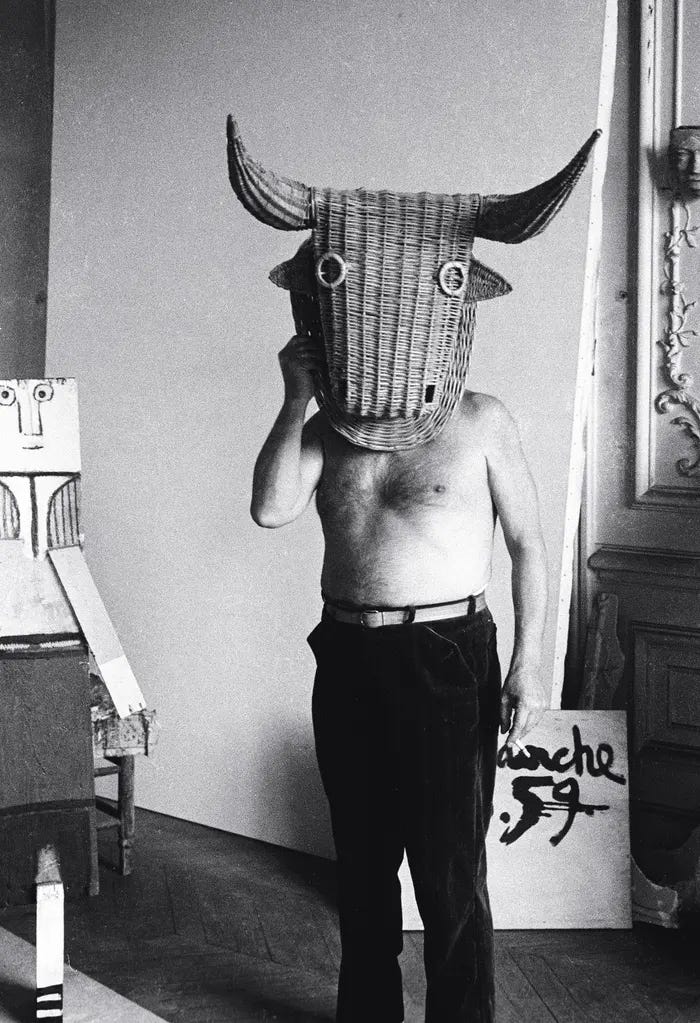

By following Friedman’s policy prescriptions, Volcker set the stage for neoliberal politics. Varoufakis’ Global Minotaur would soon rise in the United States.

For the Global Minotaur to function properly, several components had to fall into place. To remain the world’s hegemon, America needed to control how other nations’ surpluses were spent. They chose to do so by enticing other nations’ capital over to their shores, meaning that the United States had to become the world’s investment bank. They needed better financial products with higher returns and lower risks than any other country. And so the government steadily deregulated the financial sector, allowing the banks to lend money like never before. The banks employed the computer technologies developed due to the Keynesian spending that underwrote the Space Race to keystroke new money into existence. They created cash ex nihilo that they would lend to people on the basis that it would allow debtors to create value in the present that the banks had assumed would exist in the future.

Bankers also began to develop innovative financial products—futures, derivatives, and other exotic financial instruments—that claimed to eliminate a huge portion of the risks associated with financial activities. These products that ensured ‘riskless risk’1 for investors were priced using formulas like the Black-Scholes equation which, in direct contradiction of Keynes’ argument that prices cannot be calculated because we do not know the future, simply asked people to assume the future would be like the past. As long as things stayed the same, the models argued, we can know the future—an idea whose logic politicians on both the left and right would adopt as they recast themselves as mere technocratic managers whose purpose was to ensure endless, stable economic growth.

With these financial products in place, American banks attracted capital from across the world. Japan and Germany, now great exporters due to America’s support after the war, sent their surpluses to Wall St. Arabic oil producing nations, too, stored their petrodollar profits in American banks, giving America an incentive to engage in a range of imperialistic actions to ensure that there was no disruption to the supply of oil to the world and Arab capital to their banks—a practice that would have disastrous consequences in later years. The banks could then use this capital as they wished to make their profits, creating all kinds of financial instruments and exotic derivatives, loaning it out in the form of credit cards and mortgages. The stock market boomed as a response, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average rising from 3,464 points in January 1980 to 21,016 points by December 1999.2

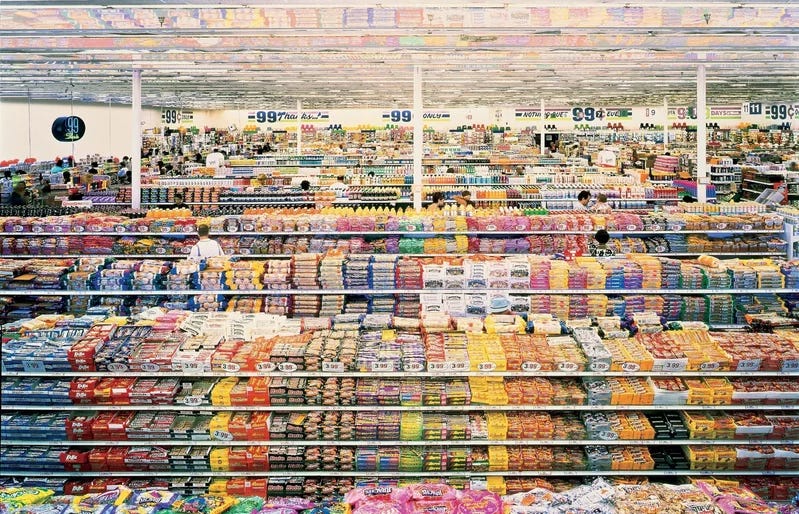

As ever, debt-driven capitalism still required endless growth to sustain itself. To support this continued growth, as well as bolster other countries’ export surpluses that would be stored in Wall St banks, America needed to become the world’s great importer. The formerly repressed energies of desire unleashed by the bomb—energy that seemed to possess such radical potential in the 1960s, that theorists from Wilhelm Reich to Herbert Marcuse believed would liberate us from capitalism, that artists like Bowie and Kubrick harnessed so effectively—was gradually channelled into the ‘controlled circuits of the economy’ in a process Foucault called ‘hyper-repressive desublimation.’3 Instead of fuelling political revolution, the energies liberated by atomic bomb nihilism fuelled consumption culture. They supported capitalism. Sexually liberated, corporate interests co-opted our desires, guiding us to use credit cards to buy endless amounts of goods we could not possibly need. ‘Enjoy yourself!’ soon became a command; intense euphoria, our most treasured experience. And, in our world of ‘controlled disintegration,’ we were soon consumed by what we had set free.

References

Foucault, M. (1978) The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. New York, Pantheon Books.

Marcuse, H. (1966) Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry Into Freud. Boston, MA, Beacon Press.

Marcuse, H. (2002) One-Dimensional Man. London, Routledge Classics.

Varoufakis, Y. (2015) The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the World Economy. London, Zed Books.

Footnotes

The Global Minotaur, p.5.

See https://www.macrotrends.net/1319/dow-jones-100-year-historical-chart

The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, p. 114. See also Eros & Civilisation and One-Dimensional Man.