Human capital theory has refashioned our world. To pervert one economist’s words, ‘to omit human capital when studying American ideology is like trying to explain Soviet ideology without Marx.’1 Given its importance, intellectuals that defend the status quo must uphold this theory. To protect Western civilisation, they must reify narcissistic self-exploitation. They must promote an ambitious mode of being – the economy demands it.

Jordan Peterson’s philosophy of potential is not merely about human well-being. In our historical moment it also promotes the narcissistic self-actualisation central to human capitalism. Like Becker’s theory, Peterson’s philosophy of potential describes and opens a schism within us. It transforms narcissism into a natural condition and elevates it into an aspirational ideal. Peterson’s commitment to total-work, we see, is both an ethical commitment to such narcissism and a symptom of human capitalism. Meanwhile the ‘addiction to possibility’ he valorises underwrites our new totalitarianism of the soul. It directs us to sacrifice all other possibilities for living as we relentlessly try to merge our ego and ego-ideal.

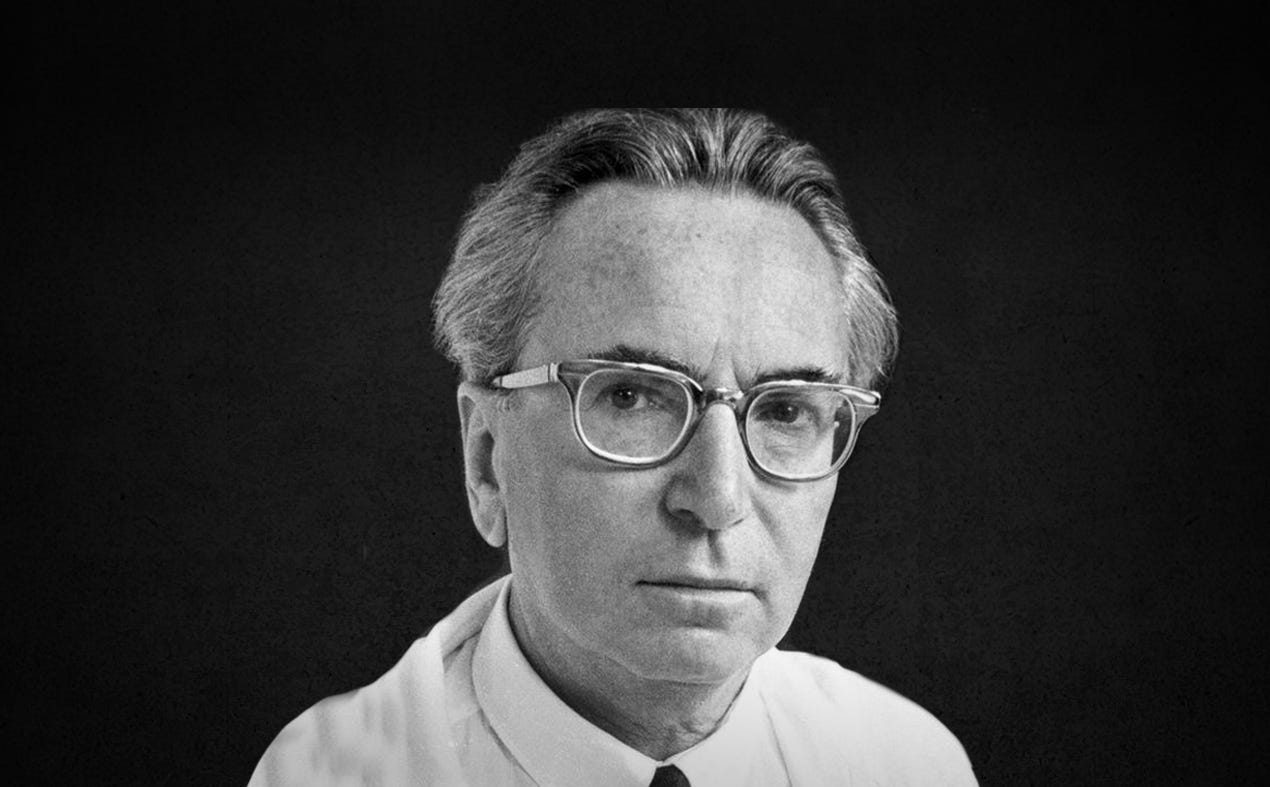

A leading neoliberal ideologue, Peterson reaches deeper into the human soul than life coaches and other proselytisers of potential. He justifies his vision of the split, narcissistic self by deferring to authorities like Nietzsche, Piaget and Jung. Of his predecessors, however, none are so important as Viktor Frankl. Frankl is most famous for his Holocaust memoir, Man’s Search for Meaning. As many readers have recently discovered—in some cases due to Peterson’s ‘Great Books’ list—Frankl’s book is an intensely hopeful work.2 Peterson’s interest in it comes not only from its bleak illuminations of the concentration camps, though. More important is its second part where Frankl explains his theory of ‘logotherapy,’ which says our search for meaning is our ‘primary motivation’ in life.3

Logotherapy is a forerunner of Peterson’s own narcissistic ideology. Human well-being, Frankl insists, depends on the struggle for a meaningful life. Against people like Freud, whose works before 1920’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle said humans were driven by the desire for pleasure, Frankl believed we have an intrinsic ‘will to meaning’ that we satisfy by ‘struggling for a worthwhile goal’ like love, creativity or finding dignity in suffering.4 Meaning sustains us. There is ‘is nothing in the world,’ Frankl says, ‘that would so effectively help one to survive even the worst conditions as the knowledge that there is a meaning in one’s life.’5 If we commit to the struggle for meaning, we flourish. If not, we descend into suffering, misery and death. So goes Frankl’s recipe for surviving the Nazis’ concentration camps.

Some readers of Man’s Search for Meaning (including my partner, Nicola, who originally drew this to my attention) identify a latent narcissism in Frankl’s account. Frankl argues that those who were able to find meaning in their lives were more likely to survive the Holocaust. He thus makes survival in the murderous concentration camps a matter of individual will, of one’s capacity to fixate on their ideal of meaning, instead of chance and abject sadism. Frankl effectively blames the victims for their deaths, then, and positions himself, the heroic theorist of meaning, as superior to those who died because they could not hold on to meaning. Perhaps, then, the narcissism of Frankl’s theoretical system is no accident. Indeed, as Lawrence L. Langer writes on pp.24-26 of Versions of Survival, Frankl makes ‘survival a matter of mental health.’ As such, it ‘comes as no surprise to the reader, as he closes the volume, that the real hero of Man’s Search for Meaning is not man, but Viktor Frankl.’

To find meaning and health humans need the stress produced by what Frankl calls our two-sided ‘polar field of tension.’ The ‘polar field’ is the existential space born from our search for meaning. The man called to pursue meaning in life stands at one end of the field, while the field’s other ‘pole’ holds the ‘meaning that is to be fulfilled’ by his actions.6 The polar field’s tension emerges when man’s ‘transcendent conscience’ issues the ‘call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him’ to his conscious mind,7 inspiring him to close the gap between what he has achieved and must still accomplish. Listening to our conscience, while not mandatory, is vitally important. Reducing the gap ‘between what one is and what one should become’8 reduces our neurotic suffering. It gives us the meaning that might sustain our life.

The logotherapeutic concept of humanity is simple. It says there is man and his vision of meaning, and that man must strive to become one with his vision. It also insists that the manifestation of this possible meaning, this potential, is vital to health. Many people find an intuitive appeal in this idea. Whether our meaning-fetish is necessary or ideological, most are familiar with the desire for a ‘meaningful’ life. But with our knowledge of human capital ideology, we also see the rift in the heart of logotherapeutic man. Like a self-entrepreneur Frankl’s man is divided. He is a mirror image of the narcissistic human capitalist. Like the latter, who is comprised of a manager-self/ego-ideal and worker-self/ego, part of Frankl’s man calls him to meet his potential. Another part of him obeys that command.

Frankl’s work is not merely rationalised psychopathology. The self-exploitative human capitalist can subscribe to it without reservation, though. The will to meaning can seamlessly become the university graduate’s narcissistic will to meaningful work. The yuppie can skim the memoir on his lunch break as he devises his five-year plan or read it by lamplight after he swallows his SSRIs. At all times he will find his life justified within its pages. So generic and flexible are Frankl’s encouragements for us to find our ‘specific vocation or mission in life,’ says Lawrence L. Langer, that ‘one can even imagine Heinrich Himmler announcing it to his SS men, or Joseph Goebbels sardonically applying it to his genocide of the Jews.’ Anyone can find meaning in their work if they try. If Frankl’s meaning doctrine had been ‘more succinctly worded,’ Langer writes, ‘the Nazis might have substituted it for the cruel mockery of Arbeit Macht Frei.’9 Both Frankl and Hitler could have called their books Mein Kampf um Bedeutung – ‘My Struggle for Meaning.’

When he died in 1997, Frankl had sold over ten million copies of his book. Earlier in the decade—a year before Becker won the 1992 Nobel, a year after Peterson completed his PhD—the Library of Congress named it one of the ten most influential books in America.10 Surprisingly—or not—Frankl’s story had become highly influential in 20th century Western society alongside Becker’s human capital theory. Perhaps this is why Frankl’s ideas appear almost unadulterated in another multi-million selling book – 12 Rules for Life.

Like Frankl, Peterson sees a rift in the human heart. Meaning also shields us from death and despair. The ‘pursuit of goals,’ Peterson says, ‘lends life its sustaining meaning.’ Meanwhile ‘the horror of existence’ engulfs those who fail to conform to a meaningful and ‘profound system of value.’11 Like the logotherapeutic man hacking through the brambles on his ‘polar field,’ Peterson’s boys see ‘the present as eternally lacking and the future as eternally better.’ Today they occupy a point ‘less desirable than it could be;’ therefore they strive towards a forever-receding ‘better’ point that reflects their ‘values.’12 Irrevocably torn by ambition, they also experience a painful lack without which they ‘would not act at all.’13 Between their desire and their pain, they have a will to actualise their potential—a ‘will to meaning’ in Frankl’s language. Needing meaning, they are driven into the world where they try to unite with their ideals and realise their ambitions. They are inherently predisposed, in other words, to develop an addiction to possibility.

Indebted to Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, Peterson’s work reifies the narcissistic personality structure essential to human capitalism. With its vision of men torn by lack and racked by ambition, his existential philosophy works as an ideology for our culture of potential. Today, our narcissistic ideology has colonised the idea of ‘meaning.’ Intentionally or not, Peterson has disguised this political position as philosophy. Against Sartre, existentialism is no longer a humanism – thanks to Peterson it is now a human capitalism. A narcissism, too

Footnotes

Schultz, T. (1961) Investment in Human Capital. American Economic Review, 51(1), p.3. The original words are ‘to omit them (i.e., human capital) when studying economic growth is like trying to explain Soviet ideology without Marx.’

Man’s Search for Meaning, p.121.

Man’s Search for Meaning, pp.127 & 133-138.

Man’s Search for Meaning, p.126.

Man’s Search for Meaning, p.127.

Man’s Search for Ultimate Meaning, pp.59–60.

Man’s Search for Meaning, p.127.

Versions of Survival, pp.26-28.

https://academic.oup.com/gh/article-abstract/34/3/493/2237727?redirectedFrom=fulltext

12 Rules for Life, pp.xxxvi & 303.

12 Rules for Life, p.93.

12 Rules for Life, p.93.