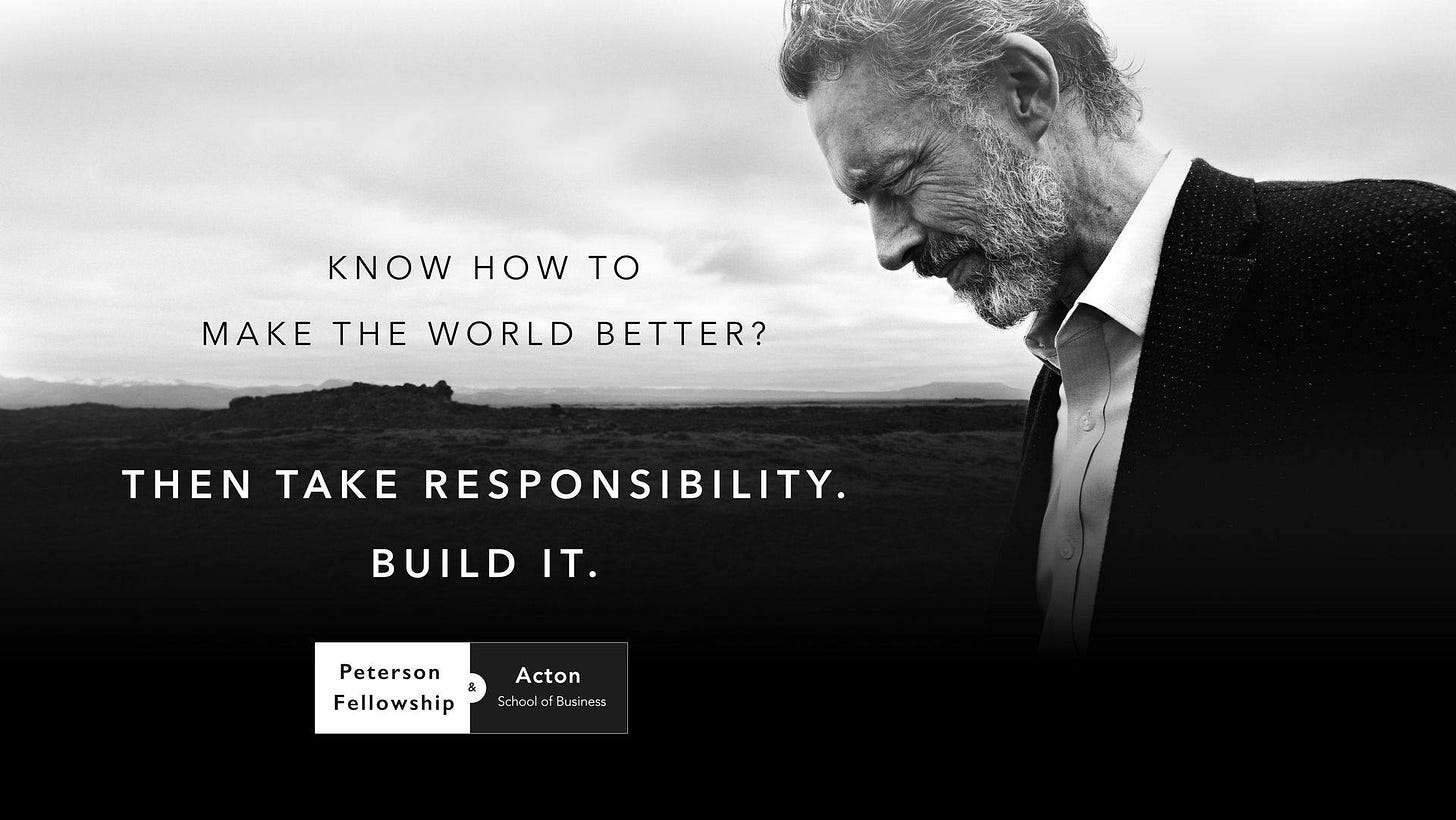

In 2019, Jordan Peterson partnered with the Acton School of Business to offer an MBA program aligned with his ‘philosophy.’ The program had ambitious aims. Like Kanye’s Gospel University, the MBA sought to train original and visionary entrepreneurs who could help Peterson build a ‘new system’ – a ‘new civilization,’ in his own words. But its true goal was more conservative. Like any other MBA it would impart to students the skills and values needed to succeed in the world of neoliberal capitalism – all for the price of $10,000 USD.1

The Peterson-Acton partnership may look like a bizarre side-hustle for a psychology professor. Instead it logically extends Peterson’s most profound convictions. An important and lucrative part of the self-development/higher education nexus, MBA programs epitomise the logic of human capitalism. If Peterson’s work implores us to cultivate an addiction to possibility, the MBA program is the benzodiazepine that slakes the human capitalist’s narcissistic cravings.

Dr Jordan B. Peterson, Defender of Western Culture and Profound Theorist of Potential, is a neoliberal. Yet we have also seen how he often espouses ideas ‘around which fascism can coagulate.’ Potential transfixes him and he fetishises the ambition each artist shows so clearly. Like the rapper and the singer, he is also an apparently contradictory figure who houses fascism and liberalism within.

An enduring belief of 20th-century politics is that liberalism and individualism are antithetical to fascism.2 Benito Mussolini himself said fascism is ‘absolutely opposed to the doctrines of liberalism, both in the political and the economic sphere.’ Given the psychoanalytic truism that people depend on what they most strongly oppose, though, neoliberalism may be less uncomfortable with fascism than we might believe. Perhaps what we see in Peterson is not the contradiction but the complicity of these ideologies.

Jordan Peterson laboured under his neoliberal commitment to potential and total-work for over thirty years. A rational little homo oeconomicus, he led a ‘hyper-productive,’ ‘hyper-efficient’ and ‘meaningful’ life. Endlessly working, we must imagine Peterson happy. But after these decades of quiet labour where he maximised the r.o.i. of his human capital, politics altered the course of his life. The ‘neo-Marxists’ arrived on the ‘battleground of [his] emotional plane.’ Hearing their calls for censorship that tend inevitably to ‘genocide,’ Peterson’s ambitions changed. A shift in the virtual, the actual, the set of futures to come. Agitating for equity, the ‘postmodernists,’ feminists and grievance scholars threatened Peterson’s vision of his potential. Anxious for his future, his society’s potential, he took it upon himself to lead the defence against ‘the radical left.’ So began his life as a public intellectual and culture warrior who calls himself a liberal but sometimes advocates for fascist ideas.

Scant biographical facts are available for long passages of Peterson’s life. We cannot say exactly why Peterson underwent his ante-fascist transition, his political identity reassignment surgery. In Maps of Meaning and 12 Rules for Life, though, he tells us how he worked for many years to understand why people commit atrocities for the sake of ideology. ‘It isn’t precisely that people will fight for what they believe,’ he says. ‘They will fight, instead, to maintain the match between what they believe, what they expect, and what they desire… people will fight to protect [the structure of meaning] that saves them from being possessed by emotions of chaos and terror.’3 In Peterson’s eyes humans do not commit ideological violence for the ideology itself. Rather our systems of belief ameliorate our anxiety. We then brutalise others to conserve the mapping between these belief systems and reality that stops chaos consuming our lives.

Violence is always conservative for Peterson. Meanwhile ideology is like Xanax – it keeps our anxiety at bay. People commit atrocities, he says, to preserve the stability of their worldview. To defend themselves against terror. With these thoughts, Peterson echoes Ludwig von Mises, who believed fascist violence was the liberal’s ‘emotional reflex action’ to communist threats.4 Von Mises thought fascist anger emerged when the ‘militaristic and nationalistic enemies’ of communism realised that liberalism had cheated them. An ‘overscrupulous’ regard for ‘liberal principles’ enfeebled the liberals’ willpower, von Mises said, leading them to tolerate toxic socialist views.5 Tolerance invited extremism and disintegration; liberals became fascist, then, to resist the communists. For von Mises fascism colonises the liberal’s future when he perceives a threat to his society and worldview. The fascists’ violence was their ‘emotional reflex’ against something that threatened their liberal ‘maps of meaning.’ Tragically, though, their defence ultimately undid all they hoped to protect. They become fascist to protect liberalism and so destroyed what they cherish.

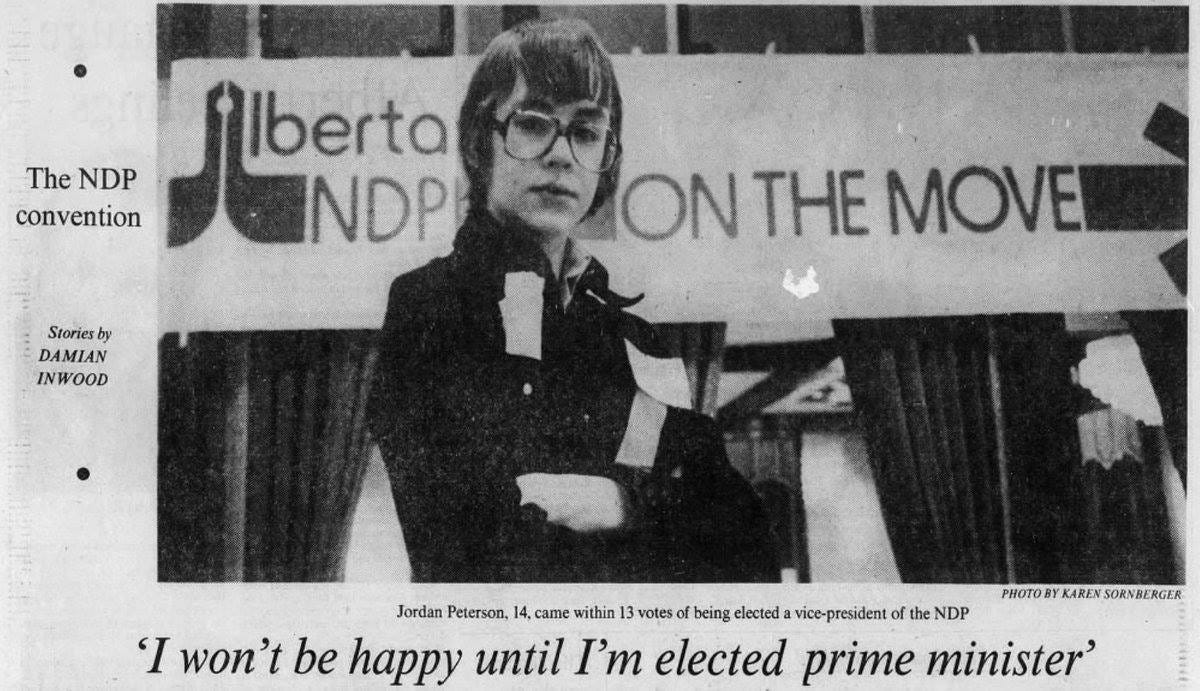

When threatened, terror changes the liberal’s ambitions, goals and potential. The short autobiography in Maps of Meaning shows that Peterson has a long history of such ‘emotional reflex actions.’ First we learn that Peterson was raised Catholic. He attended confirmation classes at the age of twelve. A perceptive and intelligent boy, he found the Catholic doctrine absurd. Soon he abandoned his religious beliefs. Unmoored ‘from the traditions that supported [him],’ Peterson found some freedom. Yet ungovernable geopolitical anxieties quickly overwhelmed him. ‘I developed a premature concern with large-scale political and social issues,’ he writes, ‘at about the same time I quit attending church.’6 Worries about poverty and eschatological fears of nuclear war consumed him. Intense political rumination preoccupied him all his waking hours. He obsessed over the potential for social collapse and cataclysmic violence.

Later Peterson attended university. He first studied political science, hoping to be a corporate lawyer. Outside of class he explored socialist student politics and sat on his college’s board. To his surprise he developed respect for the board’s ‘politically and ideologically’ conservative members, comprised of ‘lawyers, doctors and businessmen.’ Meanwhile he disdained the ‘peevish, irritable, and little’ left-wing activists who resented the rich and successful.7 Another moment of ideological collapse followed where he abandoned his nascent socialist beliefs.8 No longer Christian or communist, Peterson entered another period of soul-searching. ‘All my beliefs—which had lent order to the chaos of my existence, at least temporarily—had proved illusory,’ he felt. ‘I could no longer see the sense in things. I was cast adrift; I did not know what to do or what to think.’9

Drifting listlessly in a nihilistic world, a truly apocalyptic anxiety consumed Peterson. Deep and existential questions about nuclear war possessed him. ‘[W]hat could possibly be worth risking annihilation—not merely of the present, but of the past and the future? What could possibly justify the threat of total destruction?’10 Tortured by such grand problematics, he resolved to study psychology. But things only worsened. Aggressive urges toward his classmates and stories of violence started intruding on his mind. Fascinated and troubled by his passions, Peterson realised he shared Hitler and Stalin’s capacity for violence. A profound self-disgust then consumed him. He started feeling he was dishonest and false. Adopting a harsh and ascetic mental regime, he started speaking only those sentences his ‘internal censor’ deemed acceptable.11 At first this resolved his anxiety. The self-denial soon made him feel unreal, though. Weeks of horrible and vivid nightmares began. His nuclear war dreams became so ‘intense’ he feared they would ‘derange’ him. He started feeling depressed, anxious and ‘vaguely suicidal.’ ‘Everything I had once believed about the nature of society and myself had proved false,’ he said. ‘[T]he world had apparently gone insane, and something strange and frightening was happening in my head.’12 ‘I wasn’t schizophrenic,’13 he writes. The reader isn’t convinced of his distance from psychosis, though.

At this psychic extreme of terror, dread and disintegration, all Peterson had repressed returned. On a dark night of self-disgust, he found himself painting a picture of Christ. Perplexed, he read Freud14 and Jung to understand his unconscious. A period of profound withdrawal into thought began,15 a schizoid flight into language that eventually led to the intellectual system described in Maps of Meaning. In the crucible of anxiety, self-hate and intense mentation, then, Peterson came to his mature, ‘post-ideological’ position – his Christian, individualist, and neoliberal theory of meaning and potential.

Whatever the merit of Peterson’s intellectual elaboration, its genealogy is suspect. Peterson says his studies cured his anxieties. The ‘cure’ they wrought, though, ‘was purchased at the price of complete and often painful transformation: what I believe about the world, now—and how I act, in consequence—is so much at variance with what I believed when I was younger that I might as well be a completely different person.’16 We see, however, that the answers he found were anything but new. Instead, they represent everything he disavowed. Raised in a Christian household in a nation beholden to neoliberal capitalist individualism, Peterson’s anxious crises led him to regress and identify with these old values. Like Bowie on Young Americans, Peterson fought his disintegration anxiety by identifying with the ideals that guided him as a young boy. While he quotes Matthew 13:35 for his book’s epigraph—‘I will utter things that have been kept secret from the foundations of the world’—it seems he instead utters things he kept secret from himself.

Endnotes

See https://peterson.actonnga.org/, https://financialpost.com/entrepreneur/how-jordan-peterson-became-the-face-of-an-mba-program-in-texas and https://www.actonnga.org/the-peterson-fellowship-guide/

12 Rules for Life, p.xxxiii.

12 Rules for Life, pp.xxx–xxxi.

Liberalism, p.49.

Liberalism, p.48.

Maps of Meaning, p.7.

Maps of Meaning, p.8.

He also says that he became disenchanted with his study of political science, because it used economic ideas to explain actions, which posited that resources like commodities had ‘intrinsic value.’ This is precisely not what the mainstream economic theory taught in universities in the latter half of the 20th century says. In another moment of disavowed identification with neoliberal ideology, he says that value had to be individually, culturally or socially determined, and was thus moral. While most economists probably wouldn’t use the word ‘moral’ in their theories of value formation, the idea that value is contingent on demand and desire is exactly what contemporary university economics teaches.

Maps of Meaning, p.8.

Maps of Meaning, p.9.

We recall here R. D. Laing’s description on p.74 of The Divided Self of a highly typical schizoid personality trait: ‘The individual in this position is invariably terrifyingly self-conscious… [he has] the feeling of being under observation by the other… From within, the self now looks out at the false things being said and done and detests the speaker and doer as though he were someone else. In all this there is an attempt to create relationships to persons and things within the individual without recourse to the outer world of persons and things at all.’

Maps of Meaning, pp.9-12.

Maps of Meaning, p.11.

Once again, Peterson’s reading seems rather selective here. He says he read The Interpretation of Dreams but found it difficult to accept that his anxiety dreams could be ‘wish fulfilments’ as Freud had postulated. This is fair enough: but why did he not then read Freud’s papers on anxiety, written after Beyond the Pleasure Principle, where he provides an alternative theory of anxiety dreams?

We are reminded here of Freud’s comment on p.96 of ‘On Narcissism’ that narcissistic self-scrutiny furnishes one with the intellectual material needed to construct ‘speculative systems.’

Maps of Meaning, p.13.